Hello, everybody! I just want to say that, through my diligence, I have obtained two more spaghetti westerns–and Arrow Limited Editions at that–for my home-video collection, “The Grand Duel” (1972), and “Keoma” (1976), both containing the much-prized “Special Collector’s Booklet”! As this site is filled with so many knowledgeable spaghetti-western buffs, perhaps someone could also tell me why so few spaghetti westerns have dealt with one of my favorite fields as a lifelong history buff–the American Indian Wars? Offhand, I can think of only a few Italian and other European westerns from the subgenre’s most prolific time of production, the period of 1964-76, although, in truth, the genre’s heyday had ended in 1970–“Soleil Rouge”/“Red Sun” (1971), the very historically accurate “La Spina Dorsale Del Diavolo”/ “The Deserter” (1970), among the most Americanized of spaghetti westerns (so much so, in fact, that, perhaps it shouldn’t even be classified as one), and “Ne Touche Pas Femmes (Femme?) Blanc”, an absurdist satire of the later life and Indian-fighting career of one of my greatest lifelong heroes, General George Armstrong Custer, in which history falls by the wayside in a vicious effort by director-co-writer Marco Ferreri to link the American Indian wars with Vietnam and 20th-century American consumerism to present as distortedly brutal and as ugly a picture of American history–and of America “in toto”–as has ever been so overwhelmingly propagandistically presented on the world’s cinema screens.

Historically accurate in what way? The ending is more like a scene out of The Dirty Dozen than an historical encounter between soldiers and Apaches.

I’m not sure anyone will be able to give a definite answer but if you look at the westerns that were being produced by Hollywood during the same period, there certainly wasn’t as many as the 1950s. The Germans produced quite a few and some of the earlier spaghettis imitated them. There’s more than you might have realised. Off the top of my head, there’s:

The Black Eagles of Santa Fe (German Co-production)

Pirates of the Mississippi (Germany/Italy)

Massacre at Marble City (Germany/Italy)

The Heroes of Fort Worth

The Secret of Captain O’Hara

Buffalo Bill, the Hero of the Far West

The Road to Fort Alamo (about as close to a near perfect imitation of the traditional American cavalry westerns that you’ll find)

Finger on the Trigger (a Spanish western with Rory Calhoun in his only Eurowestern role)

A Bullet in the Flesh

100,000 Dollars for Ringo (definitely a lot of Indians in this one)

The Fury of the Apaches (a very good one reminiscent of the classic American siege westerns with Indians)

Massacre at Fort Grant

The Tall Women

Later spaghettis often had Indians and ripped off American revisionist westerns. For example, there’s Beyond Hatred, Vengeance Trail, Apache Woman, Scalps, White Apache and Jonathan of the Bears.

Perhaps the main reason the bulk of spaghettis tended to feature Mexican bandits rather than Indians is because the Italians and Spaniards had managed to perfect their own style and no longer found it necessary to continue imitating American films (and imitated their own films instead!) but as you can see, there’s no shortage of Eurowesterns with an Indian Wars theme.

See also this topic

and this one

The_Man_With_A_Name–Oh no, “La Spina Dorsale Del Diavolo”/“The Deserter” (1970) is quite accurate–all of the costumes, white and red alike, are quite authentic, the depiction of the U.S. cavalry fort that is the scene of much of the film’s action is quite true-to-life in its isolated desert locale and in its internal architecture, especially post commander Colonel Brown’s (Richard Crenna) headquarters (I’m admittedly not quite certain about the accuracy of the fort’s stone walls), the courage, mastery of desert, mountain, and guerrilla warfare, and cruelty–especially towards captured white women–of the movie’s Apache warriors conforms perfectly to history, the frustration of the U.S. Army, when fighting conventionally–as, unfortunately, it did for the most part–against this tribe in its efforts even to find the Apache, let alone subdue these great warriors–is also quite true, as is the film’s implication that U.S. forces were also greatly stymied by the Apache advantage of not having to respect international boundaries, the Indians, therefore, being able to most easily flee into Mexico to avoid capture by–or even battle with–their American foe, Captain Victor Kaleb’s (the film’s antiheroic protagonist, as played by Bekim Fehmiu) usage of Apache tactics to fight Apaches parallels perfectly General George Crook’s adoption of the same methodology during the early-1870s campaigns against this tribe which helped establish the general’s reputation as one of his country’s premier Indian fighters, as the movie’s depiction of the Apache cavalry scout, Natchai (Ricardo Montalban) as a fighter against his own tribe mirrors Crook’s use of Apache scouts to do the same, and it must also be said that “The Deserter” is quite accurate in showing black American cavalrymen’s courage in fighting Apaches and other Indians–and these soldiers’ devotion to the American army–and to America–in Woody Strode’s portrayal of Corporal Jackson, even if the United States’ armed forces were not integrated at the time of the film’s action, although the work does limit its error in showing Jackson to be the only black soldier serving with his otherwise all-white unit, in its depiction of the its main villain, the (fictional) great Apache chief, Mangus Durango (Mimmo Palmara) as a most mystical, even godlike, warrior, and–despite what you say–in its final battle, which greatly parallels the defeat and death of the great Victorio himself at the hands of Mexican Army Colonel Joaquin Terrazas, also a politician, in an ambush–the method used by Kaleb’s 19th-century special operatives, after trapping the fabled chief in a canyon near the three Chihuahua mountains called Los Tres Castillos, just as the film’s heroes crush Mangus Durango and his people (Apache women and children, unfortunately, were caught in the crossfire of both of the aforementioned battles, also adding to the film’s accuracy) in a canyon overlooked by a most-forbidding cliff. (Terrazas had been accompanied until the last part of the anti-Victorio campaign by American contingents led by U.S. officers Eugene Carr and George Buell, the Mexican colonel dismissing them before the last leg of his effort, as he, as a politician, did not want to share credit for any victory over the Apache chief with anyone, let alone Americans, as anti-American feeling was running high in Mexico at this time, and, as well, as a patriotic Mexican, he did not want foreign troops in his country any more than necessary.)

To The_Man_With_a_Name and Sebastian–I thank you for the magnificent font of information in your posts, and, while I still don’t believe all that many spaghetti westerns dealing with the Indian Wars–a position with which Sir Christopher Frayling, Sergio Leone’s own (and, perhaps, official) biographer agrees, he having stated it to me in a phone conversation I was privileged to have with him–but now, thanks to you two, I know that there were far more than I ever suspected. Again, I thank you both most heartily!

It is also correct that not many American A westerns of the 1960s dealt with the Indian wars either. I think following the Civil Rights era, it had become less popular to make films which used Indians as body count fodder or depicted them as savages without giving them a hearing (Mexicans were the replacements). Those American westerns which dealt with the topic tended to be critical of ‘manifest destiny’ and killing Indians. More importantly, the Indian topic films didn’t make much money - Cheyenne Autumn, Major Dundee, A Thunder of Drums, Duel at Diablo and The Glory Guys were all relative box-office flops.

Even John Wayne stopped killing Indians in the 1960s - I think The Comancheros (1961) is the last western in which he kills Indians. In subsequent westerns his films tend to be sympathetic to the Indians, especially post surrender and in the 1970s he was usually paired with an Indian sidekick (albeit a white guy dressed up) and in The Undefeated has an adopted Indian son.

The Indian movies became briefly popular again as counterculture and Vietnam allegory movies in the late 1960s with A Man Called Horse, Little Big Man and Soldier Blue.

Yeah, I said that myself. I think that the spaghetti westerns reflect the period. If they’d have started making them in the 50s, there would probably be a lot more. But there’s still a good number (like the ones I listed).

To Wobble and The_Man_With_a_Name:

Thanks for the new information and thought-provoking analyses, but I can’t agree with all you claim. “Major Dundee”, for example, is in no way critical of “Manifest Destiny”, and depicts the Apache Indians to be as cruel as history proves them to have been, with the title character’s (Charlton Heston) Apache scout, Riago, even stating that his acceptance of Christianity prevents him from being as cruel as those of his people who have remained pagans. “Duel at Diablo”–one of the most historically-accurate westerns ever made–while rightly attacking the treatment the Apache–and, by implication, all or most other tribes–suffered at the hands of cruel and corrupt Indian reservation agents and other Bureau of Indian Affairs officials, and through white society’s prejudice, demonstrates, through the bigoted treatment the Apache give the film’s lone important female character (Bibi Andersson), a white woman captured by the Apache and mother of a child by the brave who captured her, a treatment just as viciously brutal as that which she suffers at the hands of whites–including her own husband (Dennis Weaver)–who despise her for living among the Indians–no matter the circumstances that brought her to the Apaches–that the Apache–and, by implication, all Indians–were just as prejudiced as the whites–which, again, history proves to be so. Also, the film doesn’t shy away from depicting most historically-accurate torture of whites by the Apache, and this tribe’s equally-so sadistic love of such activity. Ultimately, white society emerges from “Duel at Diablo” as the force for good in the settlement of the American West, while, nevertheless, having much to answer for in its treatment of the red man. “Cheyenne Autumn” makes no criticism of Manifest Destiny, only of white failure–and rightly so–to keep promises made to the Indian once the various tribes either peacefully agreed to live on reservations, or were forced to do so once defeated in battle, with whites–rightfully–shown as the heroes for the struggle for the west. “A Thunder of Drums”–perhaps the most accurate film ever in its depiction of life on Indian-Wars Era frontier posts–especially, of those on our southern border, and, particularly, of the more isolated ones–doesn’t depict Indians all that much, concentrating on the daily lives of U.S. officers and soldiers in the post-Civil War American West, but, nevertheless, shows the red men as foes of America to be defeated–again, most correctly, as most Indian tribes had no concept of land ownership, made war against each other on trivial provocations, and lived by looting and plundering, with the Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and the Apache, especially, proving themselves far worse imperialists than they, their descendants–and, worst of all, ignorant and/or scheming white apologists–claimed/claim the white man to be. As for “The Glory Guys”, it, too, concentrates mainly upon life at US frontier posts–and the love triangle of Tom Tryon, Harve Presnell, and Senta Berger–while nevertheless presenting a somewhat viciously-biased caricature of George Custer in the person of General McCabe (Andrew Duggan), while, simultaneously, making no endorsement of Indian culture or the red side of the Indian wars. A great deal of its climactic battle–a fictionalized account of Little Bighorn–are most commendably accurate, however.

As for John Wayne’s films depicting the red-white struggle, the Duke was no Indian-hating bigot. His John Ford westerns always paid tribute to Indian courage and showed the Indian to be every bit as much a human being as the white man, more often than not being entirely justified in going on the warpath due to broken white promises and corruption. In no way, however, do Wayne and Ford ever endorse the Indian’s culture or overall efforts to prevent white civilization prevailing in the west. These same feelings motivate John Chisum’s (John Wayne, of course) defense of an elderly Indian chief, now on the reservation and, like the rest of his people, dependent on Chisum’s cattle for food, against a white cavalry sergeant’s cruelty in “Chisum” (1970), and GW McLintock’s (Wayne again, of course) sympathy for the reservation Indians in “McLintock!” (1963). You’re quite right in claiming, Wobbles, that the Duke often had an Indian sidekick in his later westerns, such as Howard Keel in “The War Wagon” (1967); Bruce Cabot in the wonderful, underrated, factually-based “Big Jake” (1971); a great favorite of mine, Neville Brand in “Cahill, United States Marshal” (1973), the Duke personally asking for Neville Brand in this one, giving–as Neville Brand himself told me in an interview–the tough-guy actor a chance to launch a most-successful career comeback from the alcoholism that had, for years, made him mostly unemployable; and Richard Romancito–an actor of actual Indian descent, being of Taos and Zuni Pueblo heritage, not merely “…a white guy dressed up”, in “Rooster Cogburn…And The Lady”. (Was A Martinez’s character, the junior leader of “The Cowboys” (1972), a full-blooded Mexican, or a half-breed?)

You are quite right in labeling “Little Big Man” (1970) and “Soldier Blue” (also 1970), Vietnam allegory movies, but they are false allegories, for, as Douglas Brode writes in “The Films of Dustin Hoffman”, the former film was not a true depiction of history, but merely a reversal of cliches that only created new cliches, and further states that, in the film, Custer (Richard Mulligan) is only depicted as a caricature, and not as “…the colorful, flamboyant, and, above all, complex man history tells us that he was”. In fact, even the extremely anti-Custer historian, S.L.A. Marshall, in his “Crimsoned Prairie: The Indian Wars On The Great Plains”, states “Little Big Man”'s portrayal of Custer is merely “…(a) caricature”. “Soldier Blue” is also grossly unfair in its view of white society and the U.S. Army, with director Ralph Nelson forgetting his own good advice about prejudice, given in his earlier–and far superior–“Duel at Diablo” (1966), that “…it cuts both ways.” Thankfully, both films bombed, John Quade, the late, great devoutly Christian-conservative-capitalist actor–and activist–personally telling me that about “Little Big Man”–the source novel by Thomas Berger actually being very pro-Custer while being sympathetic–but not uncritical–of the Indian, showing him as courageous and uncompromising, while also being capable of breaking treaties, just like the white man–and also adding, I saw it twice, just to see if there was, in fact, anything of value in it, but there wasn’t." Both films should be seen as manifestations of the “woke” liberal mentality of their time, but the last film you cite, “A Man Called Horse”–again, a film of 1970, obviously THE year for pro-Indian films!–a film paralleling the actions of many of its time in seeking out new and different lifestyles, is a true classic–and another one of my great favorites–in that its makers strove to make it an historically- and anthropologically-accurate presentation of Indian life before the unstoppable coming of the white man–and succeeded brilliantly. Jack DeWitt, it author, sent me a letter I will always treasure in which he described his most-painstaking work on this most-memorable film.

No discussion of films of the Indian wars would be complete without mention of “Custer of The West” (1967) and “Ulzana’s Raid” (1972). Both were pro-white, with Custer (Robert Shaw) in “Custer of the West” seen as the courageous soldier who greatly respected his Indian foe that he was, while also portraying him as a man with human flaws and doubts, and the Indians as being, quite often, wronged by the whites and, on these occasions, being justified in warring against the whites, while, simultaneously, practicing a barbaric and imperialistic lifestyle; it may have bombed overall, but I remember the local theatre showing it in my hometown of Waterbury, CT., being packed when I saw it; “Ulzana’s Raid”, another Vietnam allegory, also depicted Apaches being wronged by whites, while nevertheless showing the pre-Christian Apache to be an inhumanly cruel being living an often morally-abominable lifestyle who had to be defeated for true civilization to take hold in the American Southwest and Mexico by a white foe who, in order to effect this, had to be as harsh as a Christian humanity would allow him to be. Although highly praised in its day, and now seen as the classic that it is, with some critics proclaiming it the best film ever made about red-and-white relations, it too bombed. I must also say that “The Deserter” can also be seen, either intentionally or unintentionally, as a Vietnam allegory, with its group of cavalrymen clandestinely entering Mexico to crush an Apache foe that has long used our southern neighbor to attack America with impunity greatly paralleling both open and secret American invasions of, and raids into, Cambodia and Laos to root out ruthless North Vietnamese and Viet Cong enemies and their allies who arrogantly–at best–violated international law by using neutral Cambodia and Laos as bases to attack American and South Vietnamese troops–and, most cruelly, civilians as well–in South Vietnam.

It failed by showing Mandan rituals instead of the Sioux Sun dance.

How so? It’s a great film but the combat is anything but accurate. Chiricahua Apaches didn’t charge large enemy groups on horseback.

To The_Man_With_A_Name–In his letter to me, Jack Dewitt stated that, in researching “A Man Called Horse” (1970), he paid a visit to The American Bureau of Ethnology in Washington, D.C., and spent a great deal of time studying the customs, costumes, weapons, rituals, and music of the Sioux Indians, and also drew on the research of the hunting/scientific expedition of Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied to the Great Plains region of North America, this Teutonic nobleman recording–in the most minute detail imaginable–the customs of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and numerous others–including the Sioux. Accompanying him on this expedition was a young Swiss artist named Karl Bodmer, whose paintings of that which the prince studied and recorded are considered–and have been for almost 200 years by leading authorities–to be among the the most accurate and detailed depictions of so many facets of Sioux and other Indian life. Director Elliot Silverstein, in making his 1970 classic, had a Sioux historian on location with him to ensure accuracy. Furthermore, “A Man Called Horse” was used, during my time at Providence College, by the institution’s anthropology department as a wonderful study of anthropological-historical realism. Obviously, all of these experts would have caught the non-existent error you point out.

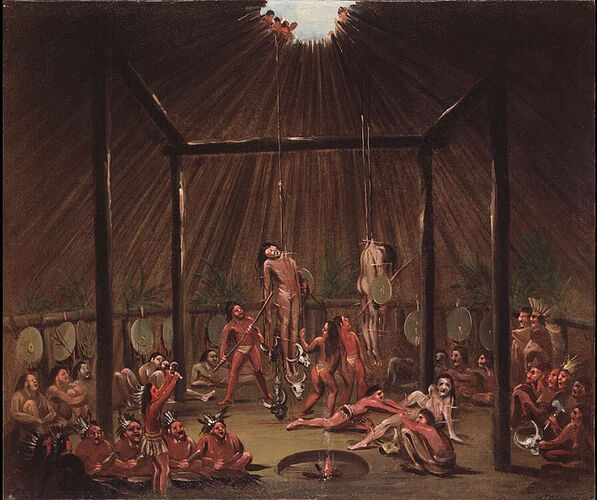

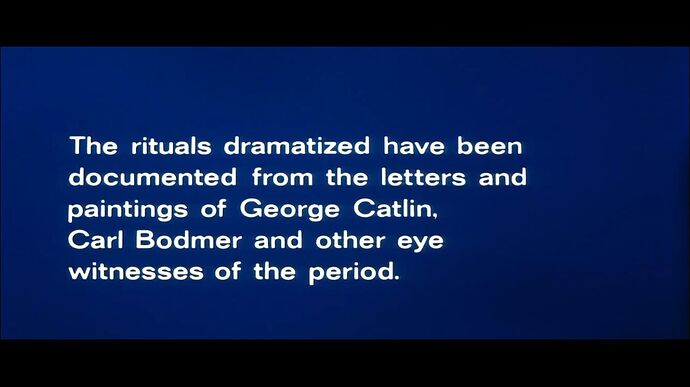

Non-existent? The sequence was based on the paintings of George Catlin depicting a Mandan ritual. It didn’t exist among the Sioux. ‘Return of a Man Called Horse’ revisited the sun dance and presented it more accurately.

As I said in my post–and as is said in the introduction to “A Man Called Horse”, Karl Bodmer’s paintings depicting the sun dance were the inspiration for the movie’s ritual. It’s been awhile since I’ve seen the film, but I believe the statement reads “…paintings by Karl Bodmer and other artists…”, although no other artists are credited by name. That Karl Bodmer’s paintings were the major–if not only–influence upon the movie’s depiction of Sioux rituals is not to be doubted, given the credit given them at the film’s beginning, the historical documentation for Bodmer’s paintings being among the most faithful depictions of Sioux rituals and life, and Mr. DeWitt’s own letter to me describing how Prince Maximilian von Wied-Neuweid’s expedition to America–undertaken specifically to study Indian cultures provided major research materials for his screenplay. Catlin is never credited in either the film’s introduction, nor in the aforementioned letter, and I notice you don’t dispute any of my evidence that the movie’s sun dance is an authentic Sioux, not Mandan, ritual. Besides, several sources I’ve read identify the Mandans as comprising a branch of the Sioux tribe.

I do dispute it. The film was criticised by American Indian communities for this very reason. I’ve also read the works you’ve mentioned and I have seen the paintings myself. The Mandan are not part of the Sioux tribe at all, they only speak a Siouan language, which isn’t the same thing.

The sun dance was accurately depicted in the sequel, ‘Return of a Man Called Horse.’ The ritual shown in the first film depicts the Mandan Opika ceremony.

Sioux Sundance:

Mandan Opika (painting by Catlin):

Catlin is indeed credited:

Dear Man With A Name,

I apologize to you for saying Catlin is never credited in the film “A Man Called Horse” (1970) for his contributions to the research materials used by screenwright Jack DeWitt in crafting his screenplay for this classic film, as you have proven me wrong. (I love this movie, but it’s been some time since I’ve viewed it.) However, I still hold to my claim that the Sun Dance Ritual is indeed most accurately depicted in this movie, as–as I have pointed out–the Providence College Anthropology Department showed the film when I was an undergraduate there as a most accurate study of the lifestyle of the Sioux Indians–Providence College’s anthropology professors being a most-exacting group of scholars, as I know from experience–Mr. DeWitt made no mention of the rite being a Mandan, as opposed to a Sioux one, and, as I’ve pointed out, an actual Sioux historian was kept on the set at all times to ensure accuracy, and, being a most conscientious scholar, would most certainly have pointed out the most egregious error of a Mandan ritual being passed off as a Sioux one, and, what’s more, a Sioux Indian who acted in the film, at a memorial held for Richard Harris several years after the great Irish actor’s death, praised Mr. Harris for his great courage in making the film. Would a Sioux Indian who felt his ancestral culture had been as inaccurately–and, therefore, as laughably–depicted as you claim–fly all the way to England decades after the making and initial release of the movie to pay tribute to the star of a film that had–as you again claim–so bald-facedly presented such a false picture of his tribal culture as it had once existed? Also, I will agree with you that the Mandan are not a branch of the Sioux tribe, but merely speakers of a Siouan language, I discovering this myself independently of our discussion through studying the writings of noted Indian Wars historian Robert Utley, and the “Encarta” dictionary. I must also mention that while “Cromwell” (1970), a movie Richard Harris made shortly after completing “A Man Called Horse” was most gleefully derided–somewhat wrongly–for its inaccuracies, real and perceived–the earlier film received no such lambasting. Finally, Gregory Michno, author of “Encyclopedia of Indian Wars: Battles and Skirmishes, 1850-1890”, told me that he devoted a few pages to “Duel at Diablo” (1966) in another of his books, “Circle The Wagons” (McFarland 2009), saying many attacks on wagon trains did occur, “mainly with the more southern tribes, like Apaches, Kiowas, Comanches, and that the “Diablo” incident seems most related to the May 1871 attack on the Warren Freight wagons in Texas”.

It isn’t though. Examine the pictures yourself and you can see clearly that the Mandan ritual is the inspiration for the scene. In the Sun Dance, the participants’ feet remain on the ground.

If you are in touch with Michno, I highly recommend that you discuss the depiction of the Sun Dance in the ‘Man Called Horse’ films and he will confirm what I am telling you is correct. The first film depicts the Mandan ritual while the sequel, ‘Return of a Man Called Horse,’ more accurately depicts the Sioux Sun Dance.

I understand that you appreciate the film but there’s no reason to defend its inaccuracy if you actually care about history.

And yes, of course there were attacks on wagons but the combat depicted in Duel at Diablo is inaccurate since the tribe is supposed to be Chiricahua. The Chiricahua Apaches almost never charged an enemy on horseback (unless they were small in number) but would dismount and position themselves in canyons and hidden spaces.

When Michno refers to “Apaches,” he includes the Gattacka/Kiowa-Apaches who were culturally distinct from the Apaches of the Southwest and had little contact with each other. They spoke the Apache language but were culturally indistinguishable from the Kiowa. The Gattacka-Kiowa Apaches formed an alliance with the Comanche and Southern Cheyenne in 1840.

The irony in all of this discussing is that in Dorothy Johnson’s original story the tribe was Crow not Sioux and there was no Sun Dance ceremony.

Little Big Man made a lot of money at the USA box-office. It was the top western of 1970 (only western in Variety’s top 10) and made over twice as much as John Wayne’s top western. The third top western of all time at the time it was released (ignoring inflation). Soldier Blue was a flop though.

I like Duel at Diablo - the music in particular - but I dispute its historical accuracy. The idea that all of those Apaches would get themselves killed attacking soldiers in an entrenched position like that is just laughable. Plus we have the white soldiers talking orders from Sidney Poitier which would never have happened in the 1880s and an implication that he was previously a soldier in this regiment. And the worst seen of all is when the soldiers start cooing at Bibi Anderson’s mixed race child which they would have never done either.

Don’t get me started on Cromwell…I studied that period in my History A level.

Or Custer of the West - a terrible movie. Even the writer admits it was made up as it went along as they didn’t have a script.

I think it was intentional since the majority of the English population supported King Charles and the filmmakers didn’t want to denigrate either side. The English are less sensitive about our Civil War history than Americans because the politics that divided people then no longer have much relevance. Cromwell has always been a controversial figure but I think the filmmakers did their best to explain his motivations and at least sympathise with him to a certain degree. British filmmakers don’t usually go for totally heroic portrayals. As a nation, we are quite self-critical and this is reflected in many historical epics that were produced during the 1970s. A Bridge Too Far (1977) and Zulu Dawn (1979) are films about British failure and in Waterloo (1970), a film about British victory, Wellington still comes across as a complete snob, which is undoubtedly accurate, but it says a lot about the way we conceptualise our past.

Richard Harris’ passionate performance in Cromwell is very unlike the actual man. The historical Cromwell was said to be rather quiet and intuitive. I still love it though. The history is confused and jumbled around but you still get the essence of the times.

I’ve read Bernard Gordon’s account of the making of “Custer of The West” in his autobiography and even interviewed him personally about it. He never mentioned that the film was made up as production progressed, as you claim. He did tell me, however, that it was far more successful in Europe than in America, and acclaimed for its historical accuracy. A biography of Robert Shaw also makes no mention of the slapdash production of which you speak. Furthermore, Professor Gregory J.W. Urwin, the author of “Custer Victorious”–long considered the definitive account of Custer’s Civil War service–agrees with me that “Custer of The West” is 78% historically accurate, although further agreeing with me–after I had admitted to him–that one must make allowances for its intentional combinations of characters and events, somewhat frequent depiction of events in improper order, and Mr. Gordon’s confession that some historical actions were distorted–or, in some cases, created–but, as my research has proven to me, not entirely without historical basis–to make use of the Cinerama process to give the film the aura of a screen spectacular. As for “Little Big Man”, noted Hollywood character actor–and even more noted Christian-conservative-capitalist activist John Quade–told me it bombed, and you don’t need me to point out–although at a future date I will–its many inaccuracies–and downright lies.

I am not going to engage with you any more after this post as you are deliberately sprouting nonsense. ‘78% historically accurate’ eh? That’s very precise.

Little Big Man took £15m in USA gross rentals in 1970 and was a big box-office hit. It is easy to check. Look up Variety.

Custer of the West is riddled with ridiculous historical inaccuracies including attributing Custer’s defeat to the impetuous actions of a fictional junior officer. In my view it is intended to be seen on an allegorical level (one symbolic general, one symbolic anonymous Indian chief, Custer an anachronism to be replaced by a machine) rather than a realistic basis.

Gordon discusses the script problems on pp 212-217 of my copy (2000 paperback edition). He says on p. 215 that there was ‘only half a script’ when Siodmak turned up to start shooting. On p 215-216 he says that Julian Halevy and himself ‘tried to keep one scene ahead of the shooting’. That is why it is so episodic and has scenes that don’t follow each other. Gordon is gobsmacked at some of the favourable reviews especially the one which claims he did years of research into it. (p. 220)

Indeed, the film is a complete fantasy. There’s a few brief moments that are loosely based on historical events but the majority of the film is pure fabrication.

The Indian chief is credited as Dull Knife, a real life Northern Cheyenne who wasn’t even present at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.