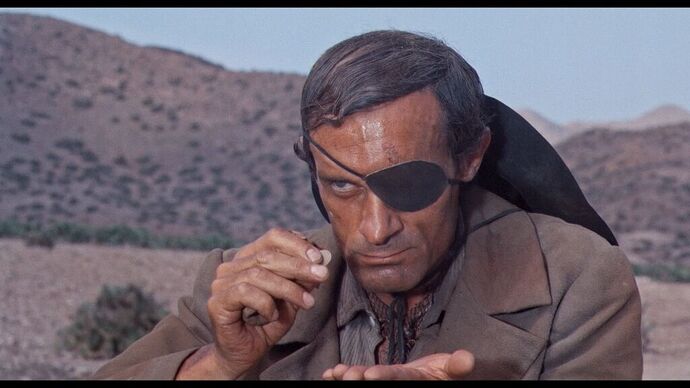

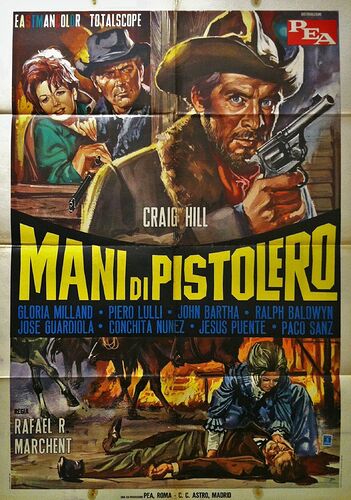

Ocaso de un pistolero (1965) - Director: Rafael Romero Marchent - 6/10.

Though the motion picture might be on the old-fashioned side, this aids the movie in that the script tends to accentuate the character development and the dramatic component at the expense of the habitual action filler, which is not to say that it likewise forgoes violence and some genuine nastiness because it includes plenty of that too; the end result turns out quite gritty and gratifying in spite of the pre-Leone stylistic proclivities. The opening scene is splendid and forms an excellent point of departure, then the narrative sort of slows down, but not to an excessive extent. The general storyline does not appear all that unconventional, however, the multiple points of strife between characters render the narration suprisingly taut and three-dimensional and afford Craig Hill a chance to act.

Hill does not squander that opportunity and turns in what might be the finest performance of his career in the genre, so much to his credit, the potential of his part is fully exploited here. In addition to the aforementioned complexities, the tragic development and protagonist’s gradual relapse into the vicious spiral of violence further boost the multifaceted nature of the tale and render the viewing quite memorable and captivating; the trenchant pessimism manifesting in the way the flick unfolds, in the manner in which it approaches the theme of human nature and in the way the story eventually climaxes seems to prognosticate the subsequent developments in the genre and in light of that, the opus becomes all the more substantial and meaningful in its own right.

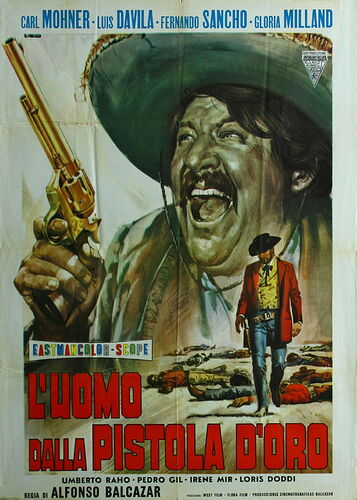

L’uomo dalla pistola d’oro (1965) - Director: Alfonso Balcázar - 7/10.

Contrary to the popular opinion, I fail to sense much in the way of an American feel and I find the entirety of it to be unapologetically Italian in its overall disposition, style and atmosphere. Though the trajectory of the narrative oftentimes proves somewhat tortuous and might appear a tad disjointed at times, the story is effectively bound together by the gripping premise: in order to evade the law, the main hero assumes the identity of a dead man who unbeknown to him, was some kind of renowned gunfighter. In spite of being a common crook, the protagonist eventually ends up living up to the reputation of the deceased man also by reason of him beginning to identify with his newly adopted role. Some of the auxiliary plotlines unfold in bizarre directions, but this trait actually comes to work to film’s advantage in that it conduces to storyline’s unpredictability, which does not manifest in the way the work ends, but rather in the way it arrives at the tale’s conclusion.

Hence, the principal narrative strand relating to the protagonist ensures cohesion, whereas secondary motifs introduce novelty and vigor into the equation. Sancho puts on possibly his funniest and most spirited performance out of all his appearances in Italian oaters; in spite of the hilarity of his acting exploits here, his part is far removed from the comic relief character trope and it might be one of the most cruel depictions of a Mexican bandit he ever enacted. Lastly, Balzacar’s direction turns out surprisingly solid in that numerous scenes visually exhibit a certain cinematic depth, whereas action sequences display much energy and vim in the way they are staged and cut; the storytelling, barring a couple of unnecessary jitters, is entirely satisfactory and moves at a gratifyingly expeditious pace. All in all, far and away Balzacar’s finest contribution to the genre and one of the best Italian westerns to come out of Italy in 1965 in my humble estimation.