“ When I started using dynamite, I believed in many things… all of it! Now, I believe only in dynamite.”

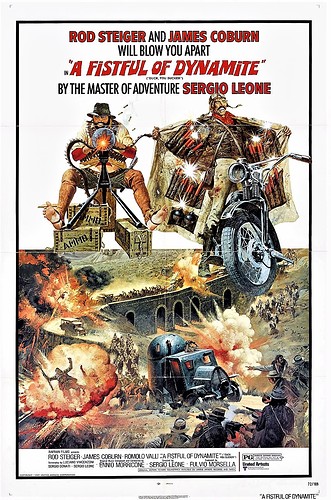

These words though uttered by a tired John Mallory, sum up Sergio Leone’s position on a number of issues. Similarly, Duck, You Sucker! (although not intended to be a political movie) sums the position of the film-maker on a variety of topics including the revolution.

It is not for the first time that we find Leone’s characters placed in a tumultuous ‘event’, while they seek to fulfil their lust for gold. A Fistful of Dollars has Joe in San Miguel where two feuding families are seeking to gain control. The Good, The Bad and The Ugly has the small matter of the American Civil War which haunts its setting, while Blondie, Tuco and Angel Eyes seek the gold hidden in the Sad Hill cemetery.

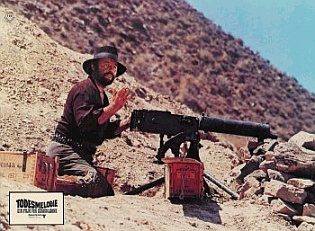

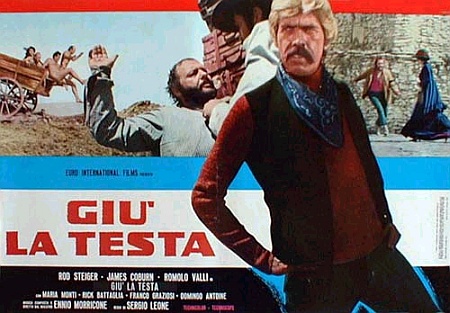

Unlike the above examples, Duck, You Sucker! deals with the ‘overarching’ event in a direct fashion. John (Sean) H Mallory, an Irish revolutionary on the run becomes involved in the Mexican revolution, while Juan, whose lifelong dream is to get his hands on the money in the bank at Mesa Verde, becomes deeply entrenched in the revolution by accident.

The movie begins with a quote from Mao Zedong (Not featured in certain versions to avoid being branded as ‘Communist Propaganda’) about how revolution is not a social event with elegance and courtesy, (wonder how revolutionaries of all backgrounds from the 19th and 20th centuries would’ve reacted to the ‘Hashtag’ revolutions of today) but an act of violence.

It explores how the ideologies and beliefs shape up individuals, impact of revolution on its participants and the relationship between individuals caught up in troubled times.

In the first few minutes, the uncouth Juan is ‘planted’ in a coach filled with upper-class individuals. It is done because this is the guard’s idea of a joke, he’d love the look on their faces when they see someone like Juan amongst them. And it surely has the intended effect.

The members of the ‘ancien regime’ include an assortment of characters with a common antagonism towards the revolution. (The Priest sarcastically remarks “… even the peasants are entitled to their rights, after all they have won a revolution, or at least almost…” ) They belong to different backgrounds and professions, there’s a lady amongst them, a man of cloth, an American, but they share the common distaste for Juan and his likes. He’s made to sit on an extendable platform, while they go about gorging on the delectable feast that is spread out for them. For them peasants are akin to animals, brutes with no knowledge of their paternity, who indulge in acts of incest and bestiality and are a plague to their country. Moreover, these traits which the peasants seemingly possess make them unfit for any better treatment, the agrarian reforms are scoffed at. They cannot be any good at anything because they are born to be not good at anything. Divine Providence/General Huerta is praised for doing away with ‘ rash individual’ Madero, otherwise he would have given away lands of the rich to ‘ these idiots’ .

The individuals in the stage-coach represent the old order that is threatened by a revolutionary act. Their understanding is informed by their social position.

On the other side of the spectrum is Dr. Villega. He is introduced on a train; his first act is to save Juan from an armed Mexican guard. In Mesa Verde, he’s shown leading the revolutionary operations, the brain behind the actors but never at the forefront. He is an individual deeply rooted in his cause so much so that even in the end he finds it tough to accept that there was much wrong with what he did, till John makes him realize his mistake.

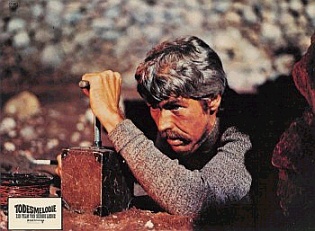

John is an Irish revolutionary, who is bitter with the entire revolution deal (when Juan inquires if he has come here to join the revolution John replies with “ No. No, one was enough for me.” ) after facing a bitter betrayal and deep mental agony over what occurred back home. Still, John is unable to help himself but join the revolutionary ongoings in Mexico.

Juan too has an interesting interaction with revolution. He’s introduced as a bandit who rapes a woman, murders people, doesn’t give a damn about anything but gold till he meets John. When he’s been tricked into joining the revolution, he isn’t entirely happy about it. His definition of his country is his family, he is not interested one bit in participating in the revolution. When John asks him to care about his country and be concerned about what Huerta and the governor are doing to it, he responds with his take on what ‘revolution’ really means:

“ The people who read the books go to the people who can’t read the books, the poor people and say, “We have to have a change.”

So, the poor people make the change, eh? And then, the people who read the books, they all sit around the big polished tables, and they talk and talk and talk and eat and eat and eat, eh? But what has happened to the poor people? They are dead! That’s your revolution! ”

With this very simplistic yet solid critique he dismantles the romantic notion of revolution. The well-to-do even if they ever participate in a revolutionary event for the ‘change’, have better chances of getting out of it unharmed as compared to the poor. To frame it in terms of a cinematic sequence, one can remember Andres Wood’s Machuca where towards the end Gonzalo is able to convince the guard to let him go by telling him to look at his clothes and his shoes.

One might disagree with Juan and this might not be true in all the cases but at the end of the day, revolution is an act of desperation. It seeks to change the existing order and needs survival of its participants to ensure its success. This ‘survival’ is usually dictated by already established financial and social norms, in which the well-to-do have better resources at hand. So irrespective of revolution’s fate, certain sections of ‘revolutionaries’ have better chances of getting out of it alive.

Therein lies an irony- most of the revolutions are about big words- dealing in ‘equality, liberty, justice’ and so on. But in practice revolution is confusion and a lot of things don’t go as hunky-dory as imagined by those who start out on this great venture. As Juan points out, the ones who face actual suppression are always the same. And its not like it gets over in one go. Juan ends with

“… And what happens afterwards? The same fucking thing starts all over again!”

Revolution might come and go, but its impact is very real on both the sides.

The tyrannical governor Don Jaime is petrified at approaching revolutionary forces of Villa and Zapata, so much so that he’s ready to part with all his money to remain alive. The sequence of him in the train is the first time we see him in person, but the viewers realize that he has been an overarching presence throughout the movie. Leone could use posters to make a special impact, Indio’s poster is followed by a maniacal laughter to show the disarray Indio and Groggy find themselves in For a few dollars more ,while Don Jaime’s posters throughout the movie symbolize his repressive regime, which has murdered hundreds and thousands.

After Juan realizes who Don Jaime really is, he sees a quick flashback with his family in the background. One couldn’t help but look back at several others who have been executed by the shooting squads of army, those killed by Gunther Reza and the hundreds of people who have been liquidated by the firing squads.

The Governor’s fears are similar to the stage-coach passengers who despised the very idea of revolution, now those fears are coming to life, as revolutionaries take over and the sequence ends with the governor being shot to death by Juan.

Leone is able to deconstruct the image of a revolutionary. Usually viewed as upright, selfless and courageous in popular consciousness, the director shows us the different facets of a revolutionary.

Dr. Villega represents the intellectual revolutionary, one who has bookish knowledge and understanding of the ‘larger issues’ that ail the society, yet at the same time he lacks the courage to commit actual acts of daring or even face the truth of an unpleasant situation. Nevertheless, once made to realize his mistake he becomes ready for the ultimate sacrifice.

Juan is someone who is thrust into the revolution, and becomes a revolutionary by experience. He enters with the idea of money, stays on for his partnership with John and later we see a transformation after the tragedy of his family. One sees him removing his cross, signifying his departure from ‘god’, not because he has studied the ill-effects of organized religion or read an intellectual debate on the issue but because he has experienced god failing him. In a later sequence, he is shown mourning the loss of fallen comrades, individuals whom he might have had little sympathy for at the beginning of the movie.

John is the disgruntled revolutionary, who finds himself yet again in middle of a revolution. (His predicament can be best described by a statement of Juan “ Seems to me the revolutions are all over the world .”) He chooses to side with the revolutionaries and along with Juan, is able to help them on a number of occasions. However, he witnesses yet another betrayal, loss of innocent lives and crushing of several dreams.

Having experienced the ‘revolution’ both John and Juan have had enough and want to continue their partnership in America before fate intervenes yet again.

The relationship between John and Juan is a special one and would be best described by the word ‘Comradeship’. The two have mutual respect and develop an understanding with each other.

When John disagreeing with the plans of the revolutionaries, decides to take the army head on- Juan decides to join him. (“ Well, if he’s gonna stay, I’m gonna stay too. I don’t know maybe because my feet are sore too, eh…” ) Later when an angry Juan has been captured by the Mexican army and is about to be executed by a firing squad, John rescues him in his usual explosive fashion.

Juan sees in John a daring comrade whom he addresses lovingly as ‘firecracker’, grows fond of him as the story progresses, even though he makes wrong assumptions about him. When they are supposed to take care of the bank at Mesa Verde or when John volunteers to stay behind and face the Mexicans alone, Juan thinks the entire idea is John’s trickery at work- wherein they’ll take the money or escape, only to realize later that he’s the one who has been tricked, though he doesn’t seem too cross about it.

John on the other hand is irritated with Juan’s antics, but decides to take him along for his revolutionary acts in Mesa Verde. He appreciates Juan’s frank opinions about the revolution which he sees closer in line with his beliefs. (The discussion on revolution between John and Juan ends with John throwing away Bakhunin’s book, to symbolize his distaste for rigid ideological incursions in many spheres of the revolution)

Trust is something that develops gradually between John and Juan and by the end they are ready to die (and kill) for each other. For John, who had seen a very close friend betray him- this is very important. A simple Juan is able to see the clarity of what revolution actually means and is able to face it straight up unlike a more complex Dr. Villega, who ends up betraying his comrades and later shows little remorse for the same, perhaps trying to run away from what he had done.

However, it is when John interacts with Dr. Villega, that they realize where the other stands. For John, it is Dr Villega’s explanation as to what happened that reminds him of his friends’ betrayal. We see the flashback where John shoots down the British soldiers who had come to arrest him and soon after he shoots his friend, who had named a number of revolutionaries including John.

The real pain in John’s mind was the death of his friend. He might have been betrayed by his friend but John couldn’t let go of his memory, the times they spent dreaming a better future for their country and dedicating themselves to a greater cause. When Villega explains that he was tortured and forced to testify, that he was still willing and able to serve the cause, it helps John understand the circumstances and helplessness which surrounded his friend. (Villega tells John at one point “ It’s easy to judge. Have you ever been tortured? Are you sure you wouldn’t talk? I was sure. And yet I talked.” )

Villega on the other hand readily understands his mistake when John utters “ I don’t judge you, Villega. I did that only once in my life. Get shovelling.” It makes Villega realize that John did not bring him there to kill him, just to contribute on a dangerous mission- given that others like Juan had been doing that on a daily basis, while Villega had not acted as a man of action.

This small event breaks him down and makes him feel the guilt for all he had done. Somewhere in the revolutionary zeal, Villega changed from the person who saved Juan in the railway carriage to one of those intellectuals whom Juan criticized by calling ‘ People who read books’ , he believed the cause was bigger and sacrifices had to be made and if he stayed alive, he could serve the cause better. He sees the folly in his thinking and owns up by making the ultimate sacrifice.

When Juan tries to revive John by talking about Dr. Villega, John calls him a “ Great, grand, glorious hero of the revolution”. The movie finishes on a grim note, with John losing his life, while Juan is left ruminating at his loss, staring at us while he says “ What about me ?” It hits the viewer with a feeling of emptiness as it ends on an intended abrupt note.

Through its many paradoxes- where Juan, a bandit is hailed as a hero, Dr. Villega, who after torture betrayed his people, being called the “ Great, grand, glorious hero of the revolution” by the very person who knew his secret, John Mallory tired of one revolution readily jumps into another, Duck, You Sucker! shows the true nature of revolution. It can mean different things depending on where one sits- not necessarily even on the opposite side and it surely isn’t the rosy, romantic solution to all the problems in the world.