A few contemporary reviews for Sergio Leone’s magnum opus ‘Once Upon a Time in the West’, mostly negative as per usual for the time. Unlike the United States (albeit briefly) the complete version wasn’t released in the UK. The truncated 144-minute cut opened at select ABC cinemas as ‘a special pre-release showing of a brand new Western’ on Sunday 10th August 1969. It first aired on UK television on Saturday 29th April 1978 (ITV 21:15 - 00:15). The original uncut version was finally released in June 1982, and played in theatres long enough for me to catch a screening aged 16 at Bristol’s Watershed in July 1985.

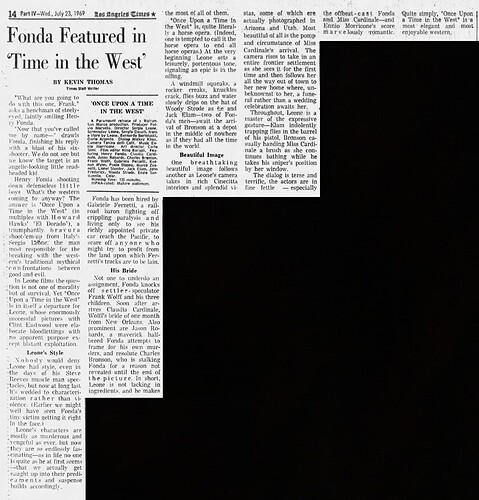

Spaghetti western triumph - PHILIP FRENCH on ‘one of the best westerns made.’

SERGIO LEONE’S Once Upon a Time in the West (Empire, AA) is being shown in this country for the first time in its 167-minute version. It is a beautiful moving and poetic film, one of the best Westerns ever made, though I have not always thought it so. Back in 1969 I was in thrall to the notion that serious Westerns represented an essential transaction between Hollywood directors, the American landscape and US history I was incapable of taking Spaghetti Westerns seriously.

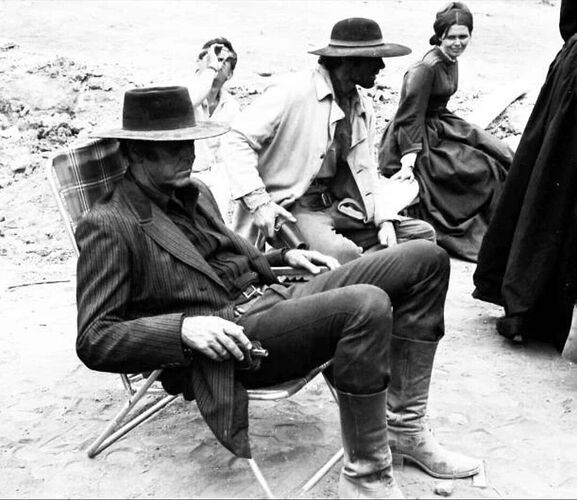

Leone made his rich, affirmative film in 1968, immediately after the immensely successful ‘dollar trilogy’ of cynical, highly stylised Westerns starring Clint Eastwood. Co-scripted by the young Bernardo Bertolucci, this long, expensive epic drew together the major themes of the genre without recourse to the sort of synoptic Reader’s Digest plot that made ‘How the West Was Won’ so thin on the prairie.

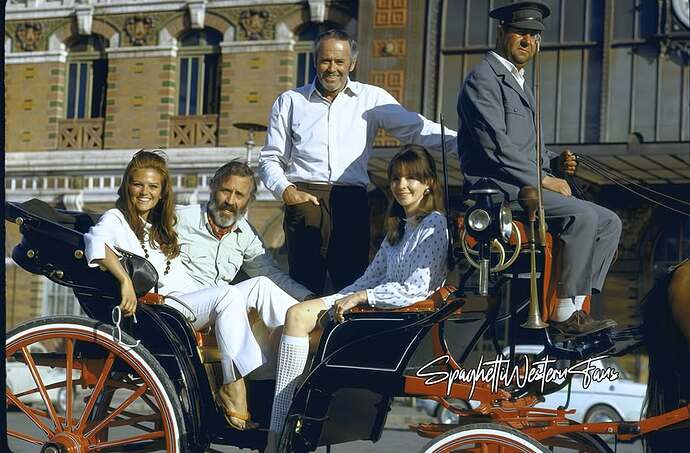

The time is vague, the period-detail very specific, the locations combining John Ford’s recognisable Monument Valley with anonymous dusty corners of Wild and Woolly Spain. Interweaved are the stories of Jill (Claudia Cardinale), a prostitute who inherits some land coveted by a railway company, the crippled railroad tycoon Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti), Morton’s hired gun Frank (Henry Fonda), an honest anarchic outlaw called Cheyenne (Jason Robards) and a mysterious avenger known simply, because of the instrument he plays, as Harmonica (Charles Bronson).

They are familiar types, powerfully embodied, both mythical figures and representatives of the historical process. In every major scene they are joined by a familiar character-actor from Hollywood or Rome’s Cinecittà (Jack Elam, Lionel Stander, Keenan Wynn among them), and they are underpinned by Ennio Morricone’s elaborate score, the theme for Cardinale beginning in an elegiac vein and modulating into an anthem of hope for the future.

The dominant motif of this film is water. The opening scene, where three killers wait at a railroad station for the arrival of Harmonica, is punctuated by the creaking of a wind-wheel and the dripping of water on to a gunman’s stetson. The ambitious homesteader defying the railroads is killed beside his well at the arid ranch he has named ‘Sweetwater’. At a sleazy saloon his bride (soon to be revealed as his widow) asks for water, only to be told by a leering bartender (providing a biblical echo) that the ‘word is poison around these parts, ever since the days of the Great Flood.’

The railroad tycoon is obsessed with reaching the Pacific before he dies, and has a seascape on the wall of his elegantly appointed railway-coach. He dies grovelling in a muddy pool, the sound of waves splashing in his mind. At the end, Cardinale goes out to the railway-workers with jars of refreshing water, an emblematic task recommended to her by the dying outlaw Cheyenne.

There is plenty of sporadic violence in ‘OUATITW,’ but Leone’s American backers were clearly disappointed with the slow, sombre, mysterious picture he delivered to them. That has so often been the way in the movies: directors from Stroheim to Cimino have failed to deliver a carbon-copy of their previous successes.

Attempting to make the film more commercial, the English language distributors added incoherence to its other apparent vices by dropping a crucial sequence in which Jill, Harmonica and Cheyenne first meet as fellow outsiders, trimming the odd couple of minutes here and there, and reducing the running-time to 144 minutes. No one complained back in 1969. After all who cared about pasta pastiches? Fortunately the film hasn’t suffered the fate of ‘Napoleon’. We haven’t had to wait half a century for a dedicated cineaste like Kevin Brownlow to restore it to us. Largely unprompted, the distributors have brought back Leone’s picture, as last year they did the complete ‘New York, New York’. (The Observer, 13th June, 1982)