It’s strange…you’d think I love the three Questi films I’ve seen because David Lynch is one of my absolute favourite directors ever. I think the difference is even Eraserhead and Inland Empire (arguably his two weirdest films) feel like they do have an obscure meaning and feel clever and poetic. The three Questi films I’ve seen just come across as bonkers for the sake of it.

Re-watched this one and much to my own surprise liked it a lot. Not sure if it’s because I watched the full-length version this time (which I know Howard Hughes thinks is inferior to the cut version) or because I was drunk. Either way I had a much better time than when I first watched it. Although I still can’t say I rate it as high as @last.caress, I think it did make its way into my top fifty. Just don’t know if I’ve got it in me to watch ‘Death Laid an Egg’ again

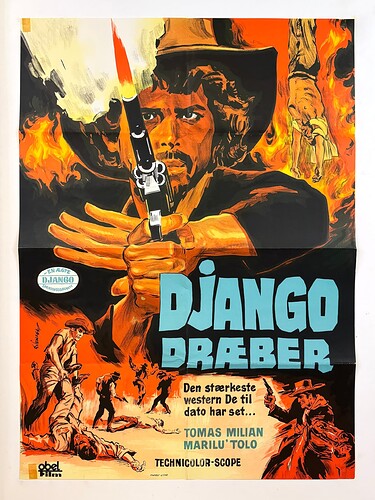

Django Kill is in my Top 10 list of favorite SWs. I read about director Questi’s background in the book “Once Upon a Time in the Italian West: The Filmgoer’s Guide to Spaghetti Westerns” and the author Howard Hughes explained that Questi had traumatic experiences from witnessing the horrors of fascism when he was younger. Further, that Questi had interwoven some of his experiences into the storyline, including religious symbolism related to his Catholic beliefs. Apparently Zorro’s/Sorro’s black-clad men were symbolic of the Blackshirts under Mussolini. As far as religious symbolism, it’s hard to miss the scene when the Stranger is tied up in a jail cell in just a loin cloth, and not see some comparison to Christ’s crucifixion. I’ve also heard that one way to look at the story in the film is that the Stranger is dead and the Unhappy Place is like a Purgatory for him to get out of through redemption by good deeds.

Funnily enough I’ve just re-read the Django Kill chapter of ‘Once Upon a Time…’ and mean to read the ‘10000 Ways to Die’ chapter tonight or tomorrow. I’ve been thinking about this film the last couple of days a lot for some reason.

Does anyone know any further details about Questi’s experiences in world war 2??

Hey, Bill. This is the best article I could find about Questi. He apparently fought in the Italian partisans at the age of 19, and witnessed a lot in the process.

Carlin, M. (10/7/19). Tales of an Outsider: The Films of Giulio Questi. Mubi.com.

Thanks, I’ll check that out.

This movie’s page in the SWDb has been upgraded to the new “SWDb 3.0” format. Please have a look and let us know if there’s something you can add (information, trivia, links, pictures, etc.)

Poll added (top of page).

Copied from SWDb General Maintenance:

It has advanced to number 4 on my SW Top list with a 9/10 rating after having watched it 10+ times in 5 years including this evening.

In spite of the, even by SW standards, weird but serious mode (which I love) I nowadays even find the detailed clever unique story consists of a chain of apparently logical events or it at least mostly possible. Surrealism, satire, allegory, sarcasms etc I think are presented in a very entertaining way in line with the general mode which the main musical theme by Vandor repeatedly emphasizes.

10/10

1 For A Few Dollars More (Sergio Leone) music Ennio Morricone 1965

1 Once Upon A Time In The West (Sergio Leone) music Ennio Morricone 1968

9/10

3 Dead Men Ride/At The End Of The Rainbow (Aldo Florio) music Bruno Nicolai 1971

4 Django Kill If You Live Shoot (Giulio Questi) music Ivan Vandor 1967

5 A Fistful Of Dollars (Sergio Leone) music Ennio Morricone 1964

6 The Good, The Bad And The Ugly (Sergio Leone) music Ennio Morricone 1966

.

Here’s a translation I did of the more interesting Q/As with Giulio Questi from the Italian audio commentary track on the Cecchi Gori DVD. There’s not one, not two, but three critics: Giona Nazzaro, Antonio Tentori and the late Antonio Bruschini. The audio was recorded twenty days before Questi’s 80th birthday. Questi’s answers are reproduced almost word for word but the experts’ questions are slightly condensed. There’s some spoilers at the end so they’re blurred out.

Bruschini: Right from the beginning of the film, we see that it has a look that’s typically more similar to a horror film than a western. We’re generally used to seeing the hero arriving on horseback with the sun, etc. Instead, it has a particular, let’s say, very bizarre beginning.

Tentori: Well, as a starting point, it’s a bit of a characteristic of this film. That, maybe there isn’t a hero in this film?

Questi: No, absolutely not. In fact, the attempt to make Tomás Milián a hero is a bit like that. Not that it works very well because it’s not even very coherent in that sense.

Bruschini: Well, yes, he’s almost an anti-hero.

Questi: Yes, absolutely. He’s condemned to be an anti-hero.

Nazzaro: Where are we here? [‘the white desert’]

Questi: This is on the outskirts of Madrid, a residential quarter was born in this place. And I found this wonderful desert that are three hills, not even high, that the bulldozers had just excavated so tearing up all the vegetation. They stripped everything that was there on these three hills, and here I set a desert. There were some problems, because sometimes it was necessary to move the camera to avoid some bulldozers that were still at work. If you look closely, sometimes you can also see the tracks of the Caterpillar that has just passed. But the effect was stupendous, so to speak. I had to stay almost always at the bottom of the three hills, because if I got up further along the slopes of the hill I could see the city beyond. Behold - it’s a magnificent desert. Because it’s white, much more beautiful than the desert of Almería; which is reddish and has a dominate pink background, which almost seems like a flaw in the film, almost like something going on a magenta pink - whereas this is a completely white desert.

Tentori: Here’s a white desert that’s now starting to turn red. Because this scene gives a little insight into the meaning of the film - for greed, for money, for hatred - this delirious carnage begins. All against all in a certain sense.

Questi: Yes, look at that handsome face [Piero Lulli - laughing at Tomás Milián’s futile attempts to fire his revolver]. But, yes, it’s certainly a tough story. But it’s also a bit, let’s say, it’s the eternal tale of the cargo of gold attacked by bandits. The dividing of the loot turns bad and leads to the violent suppression of others. A cargo of gold that’s gone up in a robbery. A fight within the band for the possession of the gold. Arriving in a village where the villagers are more bandits than the bandits in front of gold. I would say they’re all the clichés of these types of stories, it’s not that there are any particular inventions.

Tentori: Yes, however, the particular invention in my opinion, is that the western then becomes a very atypical western.

Questi: The particular invention is in the type of image, especially this one [a close-up of the bald-headed bandit], for the rest - no, let’s say, it’s just any western story. But in my opinion the particularity and success of the film is linked to the type of image, including the physiognomies of the characters. And by characters I even mean the minor actors, the extras, these generic actors who play bandits.

Bruschini: In fact, I think you told me that they were hippies that you found?

Questi: Yes, in fact, it was my preparatory work. It was very intense preparatory work in finding the so-called faces. And where did I find them? Let’s say, the ‘Mexicans’ among the students and workers who came from South America. There were Chileans, Peruvians, many of these ‘Mexicans’ were Peruvians. And I recruited the gringos among the hippies - the first hippies who came to Europe in '66. There was a colony of American hippies in Madrid who were based in the Plaza de Santa Ana; which is a well-known piazza, where there’s a bar very popular with young people and I recruited these American kids there. Plus those with the terrible faces, like this one you’ve just seen [the bald-headed bandit again], I found among the professional wrestlers - some poor wretches [poveri disgraziati] who perform in the piazze of Madrid.

Nazzaro: You once stated that the violence seen in the film was: “Inspired by the things you witnessed during the years of the War of Liberation.” [Guerra di Liberazione]

Questi: Yes, that’s absolutely true. Not in a direct obvious way, but while shooting this film and writing the story, I felt like I was talking about situations that weren’t far away. Abstract, but I felt very close to them. Because a few years before, not even that many years earlier in 1943/44/45, I was in the war. I was 18/19/20 years old in those years and I fought in the mountains in partisan formations. I was in the Brigate Giustizia e Libertà high up in the upper Bergamo valleys on the borders of Valtellina. We also went down to Valtellina. So, let’s say, the armed group that moves across a large and uninhabited territory with that kind of community which arises - 20-30 men tied together for life and death - for me these partisan bands became a bit of a source of inspiration to tell stories. This type of band moves across large territories in search of fortune and adventure.

Bruschini: I don’t know if it’s a coincidence; but when there’s the scene we saw previously of the shooting of the Mexicans by the gringos, it’s very reminiscent of a partisan shooting.

Questi: And in fact, I carried with me all the nightmares of those two and a half years of war I fought in the mountains.

Nazzaro: What do you think of this film which was butchered by censorship in Italy. And while abroad; its fame as a film, a cult film, an Italian western par excellence was achieved with expressions of esteem reaching you from the most diverse filmmakers.

Questi: Yes, this is quite true. And because, so to speak, I made the film with a certain enthusiasm. I believed in it a lot also because it was a bit of an adolescent dream coming true. Telling a story that was all my own and which was also full of memories for me. Among other things - of known violence, of known fear. Especially because the fear of death that the characters have, is the fear of death which I also had during the war. I was very afraid of being caught, lynched, shot - I have never forgotten this fear. And having to tell the story of the fury of the people, of a group of, as you might say, the guardians of the town’s morality. Here are the moral guardians of the town who express, let’s say, all the violence that comes from intolerant moralism.

Nazzaro: How did you picture these gay villains in black shirts?

Questi: The black shirts are not overtly meant to indicate fascists. And it came as a result of the situation of the story. Because these guys must have been so bad that I thought it best to dress them in black like fascists. It seemed very clear to me. In short, to be then contrasted with the white panama of their boss, señor Sorro: the owner of plantations, of farmland, of the countryside; let’s say, a landowner, he’s the typical landowner.

Bruschini: It was seized and censored shortly after about a week of release.

Questi: Yes, because the bullet and the scalping scenes were censored for reasons of public order. That’s to say, it wasn’t a magistrate who intervened, but a police commissioner. Because in a theatre, I don’t know which city, I think Milan, a couple of people felt ill. Then I don’t know who’s suggestion intervened to stop the film but the cutting of a couple of scenes was urgently requested. The scenes were cut and the film resumed immediately afterwards. It was not a court proceeding. A public order intervention, let’s call it that.

Tentori: Tomás Milián - it’s one of his first films, westerns, etc. But he already has his own form of acting, very much his own. In short, very, very intense. But he’s more controlled in comparison.

Questi: Yes, of course, because what he did in the film seemed very little to him from an expressive point of view. Because he was held fast to a kind of existential torment that he felt meant that he could have a great range of expressiveness as an actor. In fact, after this film he managed to break loose and even became the commissioner - that one, of the garbage [a reference to Milián’s character in ‘Il trucido e lo sbirro’]. [laughs] He’s had an evolution as an actor, let’s say.

Nazzaro: However, this also serves as a reminder to those who still say today that Milián, in reality, is just a gigione [a ham actor] and not a complex talent at all.

Questi: No, in fact, he came from Bolognini’s films. He also came from Italian neorealist cinema.

Bruschini: How did the title ‘Se sei vivo spara’ come about?

Questi: I remember, [the title] ‘Se sei vivo spara’ was born, thanks to Gian Carlo Fusco. He was a great friend of mine and Arcalli’s. We were searching for, let’s say, an effective title as ‘Oro Hondo’ wasn’t commercial at all for the distributor. We showed him the film and he had a lot of fun and then tried various titles. I remember it very well - Fusco, Arcalli and I were sketching out various titles and Gian Carlo Fusco came out with ‘Se sei vivo spara!’ Christ - that’s it, the title! [laughs]

Nazzaro: How many weeks did it take to shoot?

Questi: The film was broken up over time. Because I left for Spain and worked for about a month and a half in the production office of the Spanish co-producer who had taken over the production in Spain. And I worked for a month and a half to find the actors, the faces, to populate the film with significant faces. So I looked for non-professional actors, just like those American hippies, the wrestlers, etc. I then chose the main Spanish actors who lived in Madrid. And above all, I did the inspections to find the desert. Then they told me that the estimates didn’t show enough money to go to Almería to do the desert; which was a ritual that all westerns did and that was denied to me because there was no money for it. So I thought about setting it in the mountains or in the countryside. But it didn’t make sense until I accidentally discovered this construction site where there was this excavation work to build a residential quarter. After that, we started the film and shot all the parts in Spain. Then we went back and finished the film in Rome. I did some things in Manziana in the countryside and then the entire final part in Villa Mussolini. And overall it was a three-month job. Including, let’s say, that week of vacation that occurred during the transfer from Madrid to Rome.

Nazzaro: How was the public’s reception of the film?

Questi: But it was, so to speak, between dismay and enthusiasm and also a good portion of disgust. [laughs]

Nazzaro: This is a great finale.

Bruschini: Yes, completely cynical here too. The woman dies…

Questi: The prophet of liberation arrives. Without having saved anyone. In fact, not even himself…

Tentori: There’s no redemption in this western. There’s no salvation for anyone, after all, he’s basically a spectator…

Bruschini: He doesn’t take an active part that much, the only thing he does is kill señor Sorro at the end with a pistol shot…

Nazzaro: But he closes his eyes; it’s significant that in the face of such horror, he no longer wants to see…

Questi: You see her burning like a match, it’s terrible. And you see the cemetery completely desecrated and the children who continue these sadistic games, are the future citizens of the town. They’re not yet bad, but they emit the first verses of a future wickedness… [laughs]

Nazzaro: And the only concept similar, so to speak, to the classic western - the hero who rides away…

Questi: Here with him riding away utterly defeated.

The part, not mentioned here, regarding the completeness of the scene with Ray Lovelock is very doubtful.

I chose not to include the part about the gay connotations with the villains and the dubious stuff about Ray Lovelock. Some of the discussions go nowhere (including several interesting views from the critics) as Questi repeats the same answer about simply following the demands of the story.

The interview with Questi was interesting - all those rumours about other missing footage are false.

I noticed that both Cox and Hughes mention a 95m abbreviated print. This doesn’t seem to be true either as the version released in the UK was 101m not 95m. Hughes, whose book predates the DVD release of the uncut version, lists a few scenes he says were missing from the ‘95m version’ which are all scenes that would not have troubled the censor. So, a shorter version was probably prepared for English viewers as the film was too long like TGTBTU and The Big Gundown. But it wasn’t 95m.

I’m a month late but incredible interview Montero. Really interesting to hear some of his responses.

Here’s the best of the stuff not included in the earlier post.

Bruschini: This scene of the town is particular. Because with all these scenes of private violence between children, there’s even an uncle who tramples the little girl - we’ll see in a bit - it’s something unthinkable to see in cinema today.

Questi: A bad uncle is part of the tales of the great villains of the West, let’s say. [laughs]

Bruschini: Yes, however, it already frames this village as something disturbingly violent.

Tentori: It’s actually a pretext for a western. Earlier we were talking about Glauber Rocha and Jodorowsky. A western that in the end becomes a journey of initiation. Because as we continue with the images, we’ll see things even more delirious and terrible than what we’ve seen so far.

Questi: Yes, I like the term. It’s a journey of initiation into the world of greed and violence. Those who overcome certain barriers enter this world where horrible things can happen. I like the definition of a journey of initiation. Bravo.

Tentori: How did the choice of Piero Lulli come about?

Questi: Well, because he was a good antagonist. You see what a strong handsome face he has, with green eyes.

Bruschini: However, I don’t think any choice is random. Because even Tomás Milián himself was not known at the time. He had only made one other western in Spain, ‘Bounty Killer’, but in Italy it came out after ‘Se sei vivo spara’. So clearly he wasn’t chosen for that purpose. I imagine you also chose him because you liked his face?

Questi: No, for reasons, because it was already possible to make a well received film for distribution with Tomás Milián. He was already a small name that facilitated, let’s say, the release of a film.

Bruschini: Yes, he made more intellectual films, so to speak, not really westerns as he would later do from here.

Nazzaro: It seems to me to be very anticipatory of the insurrectional movements of '68. It takes charge, a good two years in advance, of a whole series of instinctive impulses which then blossomed in May '68. I don’t know if Giulio agrees?

Questi: Yes, these precise references always leave me a little sceptical. I don’t remember these close references, let’s say, on the social or political current affairs of those years. More than anything else, it was a trip down memory lane into the things I knew in the war. And the effectiveness of the film that lasts over time comes precisely from this authenticity. Because it’s an entirely made-up story with characters that aren’t part of reality, but it all seems strangely authentic. And it even seems realistic when it isn’t.

Bruschini: Yes, because there’s an autobiographical basis in everything.

Questi: Yes, it means there’s a strong and authentic participation on the part of the filmmaker.

Nazzaro: With respect to violence, did you know that you were somehow breaking the limits of permissible violence, of taboos, or was it something that came from within?

Questi: Absolutely not. I didn’t know what the limits were for me. Telling is telling, and when you tell a story, especially a brutal one, you always go a little to the core. And you always go to the extreme of things.

Bruschini: This is one of the two censored scenes. This is the extraction of the gold bullet.

Questi: Yes, it seemed like a terrible thing. [laughs]

Bruschini: In fact, it’s very realistic. But you said, you made it with simple special effects.

Questi: No, it was a piece of food I bought in a butcher’s shop that I gave to the make-up artist [Adela del Pino], who made up the meat. She made a kind of skin, with powder, with things, that’s all.

Nazzaro: How disappointed were you that they cut this scene?

Questi: Well, it bothered me a little, because then things get forgotten. But, of course, it hurt me when they cut the scalping of the Indian, which will come later, and this scene of the bullet.

Bruschini: Having already been released, however, it was further seized and censored shortly after about a week of release. It was practically a unique example in the history of world cinema. Because I don’t think there’s a western, seized and censored, so soon after its release.

Questi: Yes, because the bullet and the scalping scenes were censored for reasons of public order. That’s to say, it wasn’t a magistrate who intervened, but a police commissioner. Because in a theatre, I don’t know which city, I think Milan, a couple of people felt ill. Then I don’t know who’s suggestion intervened to stop the film but the cutting of a couple of scenes was urgently requested. The scenes were cut and the film resumed immediately afterwards. It was not a court proceeding. A public order intervention, let’s call it that.

Bruschini: Yes, I even read the absurd reason, it said: “There were scenes that could spread violence among young people”, something like that. [laughs]

Nazzaro: The figures of the two red skins who follow Tomás Milián like guardian angels, have always reminded me of those who accompany souls from Hades back to the world of the living. Because the dead have to complete a task.

Questi: Yes, that’s right. Indeed, I thank you for suggesting this image, so classic. In effect, it’s really like saying that they’ve snatched him from death, and brought him back to life. And they assist him in clashes.

Bruschini: What’s also suggestive of the film is this alternation between the realism of the images. These almost metaphysical elements. The figures of the two Indians create certain dreamlike glimpses in the film that balance the situation in a way.

Nazzaro: There’s also something of Castaneda in these two Indian shaman.

Questi: Well, yes, you’re certainly right, I’ve read Castaneda’s books.

Bruschini: There were also rumours - at least Gianni Amelio says so in an interview he gave on the history of Italian cinema - that you invented situations that are even more extreme than the ones you then filmed. For example, he says, that initially he was also expecting to see the [censored] of the boy by the bandits. And then it was you didn’t shoot it, because you said: “Okay, at this point it’s too much, they’ll definitely censor it.” And is there any truth to this?

Questi: Yes, maybe, I don’t remember well. I don’t remember if we even wanted to shoot the [censored] scene and then we gave up on it. I don’t remember exactly.

[Host Nazzaro quickly moves the discussion on but Bruschini follows-up for clarification]

Bruschini: However, nothing more had ever been filmed on the scene of the [censored]. Was it just that?

Questi: No. It’s not that stuff was filmed, which then wasn’t… No.

Tentori: There was simply the previous scene, you sense that something is about to happen. But that’s where it ends, then, there’s the suicide…

Questi: They touch the lock of hair, they’re all drunk, they look in a certain way….

Bruschini: In fact, this film is one of the westerns that’s had the most problems worldwide, I think, but certainly in Italy. But even abroad in England, as far as I know, it’s been banned quite a bit. And then in any case it was released in heavily censored versions even abroad in recent years.

Nazzaro: But then over the years Giulio fought to get the full film back. How did you fight this?

Questi: I never fought it at all. Everyone came to talk about this film - a complete edition - that they had discovered. But the film was already a distant thing for me. I didn’t even have a copy. It was brought to me again by lovers of the film - generally all young people a bit nuts in the head [laughs] - who had picked up a copy of this film. And they also wrote to me from Paris. For example, they came to visit me to do interviews for underground magazines about cinema. In short, over time, they came from Japan to make a new edition of the film. And I don’t say Japan by chance, because in Japan the film was a resounding success when it was released in '68. That’s why they’ve repressed it today on DVD and made a reissue of it, that’s one of the reasons.

Bruschini: However, in the 70s, there was also a re-release of this film called ‘Oro Hondo’, which seems to me to be similar too.

Questi: Yes, I was involved too, because in the meantime television had arrived. The film was two hours long in its original version. The commercial length for TV is one and a half hours per film. Then the producer, who was a small producer who had bought the negative, i.e. - not the original producer, the negative had changed hands. This producer wanted to make the film a success and above all sell it to television. So he wanted to make a shortened edition of about one and a half hours in the TV format. So he called me and told me the problem. I preferred to do it myself to spoil the film as little as possible. So I had it in my hands once again. I shortened the film by about twenty minutes. I don’t remember what scenes I took out. But I put back the two scenes that had been censored - hoping to get away with it. For me it was an opportunity with the excuse of shortening the film. I shortened it, but put back those two famous censored scenes. The scalping of the Indian and the scene of the gold bullet being extracted from Lulli’s body.

Nazzaro: This is a video cassette version that circulated for a few years?

Questi: So the new title was offered just to hide the bureaucratic traces of the old one. As it had to be resubmitted to the censors with a new title. And that’s the reason the new title was ‘Oro Hondo’, which was a title that wasn’t random or invented on the spot. But it was a name I gave to the script while I was writing it. It was called, ‘Oro Hondo’ - the original, right at birth. It later became ‘Se sei vivo spara’. And then again, ‘Oro Hondo’.

Bruschini: And how did the title ‘Se sei vivo spara’ come about?

Questi: I remember, [the title] ‘Se sei vivo spara’ was born, thanks to Gian Carlo Fusco. He was a great friend of mine and Arcalli’s. We were searching for, let’s say, an effective title as ‘Oro Hondo’ wasn’t commercial at all for the distributor. We showed him the film and he had a lot of fun and then tried various titles. I remember it very well - Fusco, Arcalli and I were sketching out various titles and Gian Carlo Fusco came out with ‘Se sei vivo spara!’ Christ - that’s it, the title! [laughs]

Bruschini: Well, which, among other things, because it encapsulates the film’s bizarreness! [laughs]

Questi: And so the title was born.

Bruschini: Now there’s also this torture that’s completely antithetical to the classic beatings of the western ‘Fistful of Dollars’.

Questi: No, because here everything is a bit aestheticised.

Bruschini: Yes, but also the kind of torture with these strange bat animals.

Questi: It’s more, than anything else - they’re visions perhaps, more than reality.

Bruschini: Because, then, they’re never seen approaching his body in reality.

Questi: They’re like internal nightmares. These are Sumatran flying-foxes - poor things. I shot them in Rome.

I watched Django Kill, if you Live, Shoot on Thursday and quite enjoyed it. I had seen it before on Movies for Men channel maybe 15 years back but did t stick with the poor quality haze they broadcast.

Great opinions and discussions on this thread. I think it is best to watch with an open mind and without hearing other’s strong opinions on it. I think they missed a trick at the start when they have the flashback scene of the army ambush to get the gold - this was a great opportunity for a lot of violence and action. Oakes was a great character who I would liked to have seen more of as the movie progressed. The scene where his gang enter the town is excellent and how they observe the weird situations about the town. Some good action with the elimination and execution of the gang.

The stranger is more of a passive figure and the two townsmen with the gold aren’t classic villains but corrupt and lacking morals. The Native Americans are a good addition and some interesting female parts with decent screen time for them. Sorro is a great character and larger than life and his muchachos are a great concept.

I enjoyed the movie and give it 3 stars but maybe I will watch again later in the year.

This one of a kind Italian western premiered in the UK at Broadway Cinema, Hammersmith on 11th May 1970, double-billed with ‘Dirty Angels’. Complete listings below.

Broadway Cinema, Hammersmith (11th May 70 - 16th May 70)

ABC Old Kent Road (Regal Cinema) (8th Jun 70 - 13th Jun 70)

ABC Kings, Bristol (5th July 70 - 11th Jul 70)

Futurist, Birmingham (12th July 70 - 18th July 70)

Empire Cinema, Huddersfield (12th Sept 70 - 18th Sept 70)

Scala Cinema, Liverpool (15th Nov 70 - 21st Nov 70)

Rock Cinema, Birmingham (29th Nov 70 - 5th Dec 70)

Beaufort Cinema, Birmingham (29th Nov 70 - 5th Dec 70)

Scala Cinema, Nuneaton (24th Jan 71 - 27th Jan 71)

Patrick Fleet of the Bristol Evening Post reviewed the picture during its run at King’s Cinema: Probably the best of the bunch is “Django Kill”. An Italian Western which develops into the usual riot of sadism and butchery but, at least, has half an hour at the start of some quite distinctive film direction by Giulio Questi. He evokes a remarkably sullen and brooding Mexican setting for a story of gold robbery and double-crossing among the thieves. Followers of the “Dollars” Westerns will recognise the style: Thomas Milian plays the loner who lives to plan another robbery and presumably another film… (Evening Post, 4th July, 1970)

The film returned in March 1974 as support feature to Alex Lung’s ‘King of Kung Fu’. ‘Django Kill’ first aired on UK television on Sunday 9th February 1997, BBC2 (23:10 - 01:05), preceded by a 10min introduction by Alex Cox.

Source below: (1) (The Kensington News and West London Times, 8th May, 1970)

I’m also positive that ‘Django Kill’ was shown as part of a SW season on ITV around this time, give or take a year … I remember sitting up late to record the film, as I wanted to edit out the adverts during the recording.

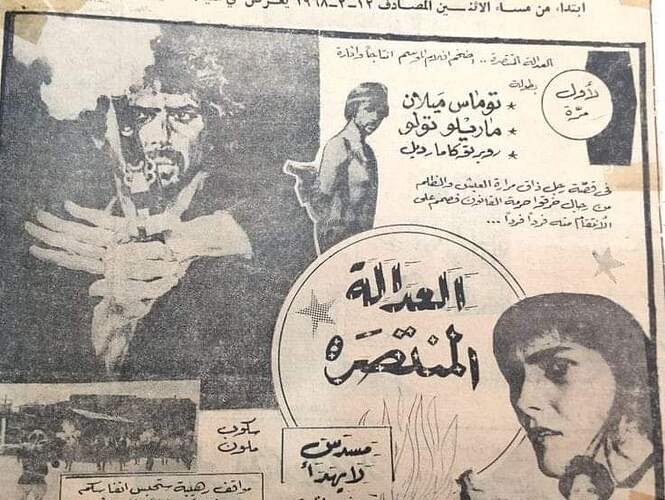

![]()