From 2011

“If anyone wishes to clarify this, be my guest”

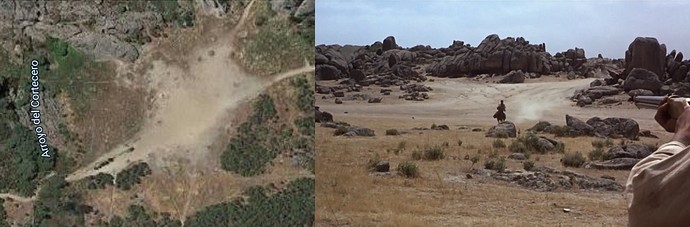

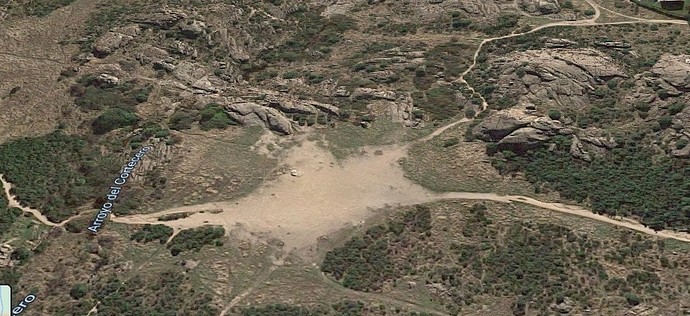

It is difficult to confirm that this is the exactly correct location where Tuco was shot at and fell down from his horse, if you like me now only use Google maps 3D. There is no “true” 3D here on the small scale of rocks. So they look distorted.

However the scene in GBU should have been shot in direction around south (since no mountains are visible), and my best guess is that the the Google picture facing south (below the GBU screen shot) contains the same formation of rocks, so it is on the area you suggested and more exactly the lower part of the right circle/oval in your own Google picture. If this choise of location is correct, then there is a lot of green vegetation now on the surface between Tuco on his horse and the background rocks.

I’m an idiot. Thanks for the frame grab. It clarified my idiocy.

This is clearly the area of Tuco’s ambush.

The frame grab is looking south, so I rotated the google map to put South at the top.

Now it is patently obvious that this is the exact location.

So what did I get wrong? I know we visited the wrong area when we first got there, even though it was El Rodaje where many movies were shot. And I know that when Don returned he went East of where we had first visited. So…

Circle one is actually where we went the first time. That was my idiot error. Circle two is the exact location of the Tuco ambush. Circle three is an area that has been used for movies, but none of us went there.

What is really spooky is that the rock that makes a superb reference point to the East of Tuco’s ambush is not alone. (This is taken from circle three)

If you are standing in circle one, you actually see a twin version of that rock on the skyline, which is why, when we first went, we thought we had arrived at the correct location.

And this is the twin rock:

So my great thanks to you for solving a twenty year mistery.

Hmm, I think there is a problem here

With south in the upper end of all examples “THREE” , Screenshot, “TWO” (in that order below) I still think that the rock formations in detail in “THREE” much better match the movie screen shot.

For example the by me marked rather substantial rock/rocks in the middle looks more similar in “THREE” to the by me marked rocks in the screen shot.

In number TWO they corresponding rocks look more flat even if the google picture “lies”. Even the rocks on the right in “TWO” look flat and smooth.

I think the open middle ground space in “TWO” might mislead and the screen shot is taken more close to the road which “falsely” appears to be very wide.

“THREE” still assumes that there is new vegetation.

There was also a “street view” on Google where you get the “TWO” area from a slithly different angle so the upper part of the picture is somewhere near south/southwest but still very relevant.

Here you clearly see that the rocks in real 3D do not match the rocks on the screen shot.

So by your definition the “TWO” area must be the correct one.

Well, I guess we’re going to need a hiking holiday in Manzanares to settle the question.

Moving on…

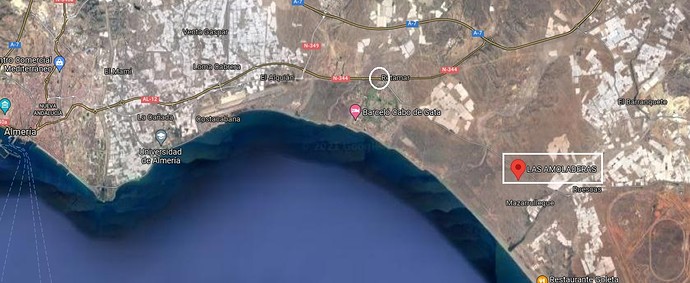

- Tuco Drags Blondie through the Desert - Cabo De Gata, Almeria

Back in 1972, there was only a narrow two-lane tarmac road paralleling the coast from Almeria to Cabo de Gata. There were hardly any houses, and the view of the sea from across the miles of sand-dunes was very clear. There was a hard sand track down into the dunes, and as you descended, the sea disappeared from view, and you could well believe that you were in a vast Arabian or Western desert, just as the film-makers who came here hoped you would.

This area was used in a host of Spaghetti Westerns besides GBU, notably BLINDMAN and THE BIG GUNDOWN, and it served Charlton Heston well for his ANTHONY & CLEOPATRA, as indeed it had earlier served Joseph Manciewicz for his more infamous CLEOPATRA, where he staged Anthony’s lone confrontation with Octavian’s Legions: “Grant me an honorable way to die”.

Leone’s friend actor/director Robert Hossein filmed his Western UNE CORDE UN COLT (CEMETERY WITHOUT CROSSES) here, and had a strange delapidated Western town built amongst the dunes. According to author Jose Enrique Martinez Moya, who called the town “El Poblado Fantasma De Las Dunas De Cabo De Gata” (The Ghost Town of the Cabo De Gata Dunes), the town was partially financed by Leone. When filming was complete, there was a certain amount of interest from various parties who wanted to maintain and use it, but being unable to reach an agreement, the owners had it burnt down and bulldozed into the sand. When I went there in 1972, I remember seeing a pile of wood and general rubbish off to one side of the track. I thought maybe it was a popular fly-tipping area (there are a lot of those near Spaghetti Western location), but it may have been what was left of that town.

By year 2000, the two-lane road had become a wide motorway, and the sea was hidden from view by new housing complexes, and endless rows of greenhouses. Don took me into Cabo De Gata, and pointing across at a dismal heap of sand surrounded by salt water and rotten with weeds said “That’s all that’s left, and it won’t be here much longer.”

It was quite a shock, but somehow I was already prepared: I had previously read an account that Olivier Billiotet had written concerning his travels in Almeria that had been published in a 1994 issue of Spaghetti Cinema, in which he stated that the desert was “useless to find today - it doesn’t exist anymore.” And that was in reference to a trip he had made in the late seventies.

It was whilst I was preparing this manuscript in 2004 that I began sorting out some colour slides of the vast desert that had existed near Cabo De Gata in 1972, and it was then that I realised how stupid I had been. Because of Olivier’s article, I had expected very little desert to be there, and when Don showed me very little desert, I just shrugged and accepted it. But now, looking at my slides, I realised that neither of them had actually been to the desert. They were all looking in the wrong place.

The desert is not to the East of Cabo De Gata village, it is to the West, now hidden by all those new houses and greenhouses. I got out my map and from the record of my slides and the depths of my failing memory I worked out exactly where it should be. Then I excitedly wrote the following note to Don:

“I don’t think you’ve actually been to the proper area of the dunes yet. In fact I know you haven’t. It bothered me at the time we went together that there was so little left. But having scanned my slides, I now have a clearer memory of the area. The place that you took me to, just outside the town of Cabo De Gata to the east, is the area that shows in my slides with the palm trees and the small salt lake in front of it. The actual dunes, which in my shots show as acres of sand is actually to the west of Cabo de Gata town, along the beach to the East of Retamar. The fact that those new roads and the greenhouses and new housing estates are all over the place makes it difficult to see the dunes anymore. But somewhere between Retamar and Cabo de Gata, you need to find some tracks turning south to the coast, (they do show on my map) and you really need to be going along the coast on the oldest road you can find. I think that Olivier Billiotet and everybody else who went out there got the wrong place because of all changes that have taken place along that road.

Those dunes must still be there. I know they are still there and you will find them.”

In 2001, Don and Marla returned to Almeria, and the dunes were still there, and they found them.

On the google map it is a place called Las Amoladeras, and it’s a small dusty track between Retamar and Ruescas. You drive down to a parking area, and then you hike to the beach. (Or a bit before the beach if you want to experience the Tuco and Blondie part).

And when you get to the beach, you get this famous view of the three peaks of Cabo de Gata which are in the background of practically every Western that has been shot in this small desert

- Monastery Exterior - Cortijo Del Fraile, Almeria

Tuco takes the sunburnt Blondie to recover at a Monastery that by now should be quite familiar to all of us Leone aficionados. But this is actually the first time in Leone’s ouvre that we see the front of the building, or indeed any recogniseable wide shot. It is the Cortijo Del

Fraile, whose roof served for part of Indio’s prison in FAFDM, and whose walled courtyard at the rear served for Indio’s courtyard at Agua Caliente in the same film.

However, the interiors of the Monastery are not filmed here, but “in a Galaxy far, far away…”

- Monastery Interior - San Pedro De Arlanza, Burgos

When Don and Marla were planning their first trip to Almeria, they asked me if I knew where the monastery was, and I told them “Italy.”

This erroneous claim was based on my memories of the interior shots of the sequence, rather than the exterior. The interior shots featured views through windows of towering hillsides covered with green-leafed trees, a lush and verdant topography which was certainly not of Almerian origin, but instead suggested to me the area around Montecelato near Rome where the famous waterfalls of so many Peplum were filmed.

I hadn’t seen GBU for several years, stubbornly refusing to have a Pan & Scan copy in the house; preferring to have nothing if I couldn’t have Leone’s original letterbox format. As a consequence, I had somehow forgotten about the dry desert look of the exteriors, which very obviously would have been filmed nowhere else but in Almeria.

However, the interiors are most definitely not filmed at the Cortijo Del Fraile, since the area surrounding the building is a dry and dusty plain, with not a tree to be seen.

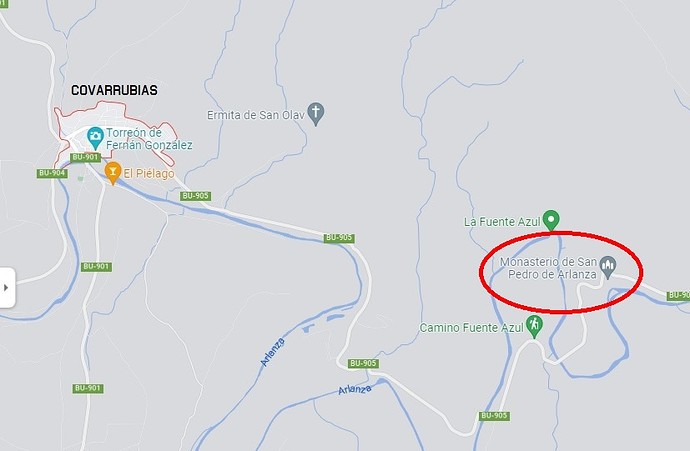

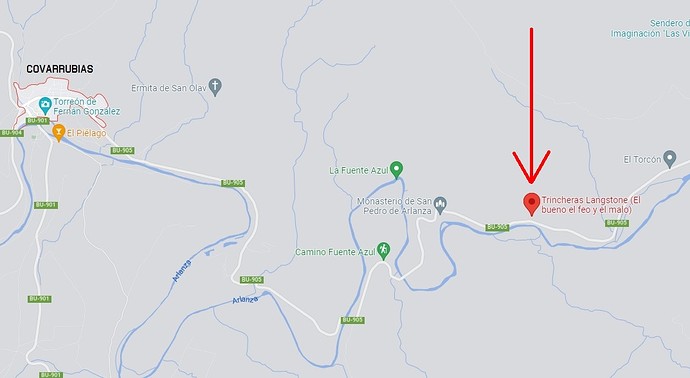

The clue to the interior location came from the fairly common knowledge that Leone had filmed his GBU Civil War scenes in the province of Burgos in the North of Spain, because he wanted an area with mountains and green forests that resembled Virginia in the USA. The name of the town of Covarrubias also became common currency when Cenk Kiral, the president of the Turkish Leone society spoke with the great Tuco himself, and Eli Wallach remembered that most of the Civil War filming had been done near this town.

Then Professor Frayling’s biography of Leone came out, and more names of likely locations in the area began to pop out of the hat, in particular the information that the “hospital interior” of the monastery was filmed at the “derelict Arlanza monastery near Burgos”.

In his final preparations for the year 2000 trip, Don sent letters to both Eli Wallach and Clint Eastwood, explaining what our expedition was about, and asking for information about certain locations that we hadn’t yet completely pinned down. Wallach confirmed Covarrubias again, and Eastwood told us that there was a monastery across the road where you could get really great wine at 5 cents a bottle.

Burgos is both a province and a City, and whilst Covarrubias is in the province of Burgos, I would hardly describe it as being “near” to the City. To get to Covarrubias from Madrid, which was our starting point, you take the main N1 motorway north. It’s 237 Kilometers if you go all the way to Burgos, but your first major landmark at 163 Kilometres is the City of Aranda De Duero. Another 49 Kilometres, and you arrive at the ancient-looking town of Lerma, which is on a hill to your right. Here you negotiate the spaghetti junction of slipways sprouting off the main highway slightly north of the town, and head towards the east, signposted Covarrubias.

For about 14 kilometres the road travels in a straight line across a flat plain of rich farmland, beyond which, impossibly high mountains appear to sprout vertically from the earth. You can tick the little red-brick villages off as you pass: Santa Ines, Bascones, Quintanilla-Tordueles, Quintanilla Del Agua. At the 14 kilometre mark you pass through Puentedura, where the

the flat grassy plains suddenly give way to towering mountains topped by white cliffs, steep escarpments covered in dense forests, and deep gorges through which the clear river winds its complex route.

Eight kilometres later you reach Covarrubias, and ignoring the main crossroads to right and left, continue on the same road for the next six kilometres as it threads its way down through a deep wooded gorge, up a steep hill, and then down into the next valley where, from a wide balcony-like curve of the road, you are greeted by a magnificent vista of the Arlanza river glistening beneath those high white mountains and dense green forests, whilst the ancient ruined monastery of San Pedro de Arlanza stands proudly beside it.

The road curves in a tight “u” shape around and slightly above the monastery before disppearing into the forested landscape; and on the right-hand side, directly opposite the building is a grassy car park, large enough for tourist coaches and cars, of which there were many to be seen when we first approached. However, there is also room to park cars in the dusty yard just outside the monastery gates, which is accessed by a short but steep track descending from the main road.

It was fairly busy, with groups of tourists bustling around when we first arrived, so we continued with our exploration of the general area and returned some time later when things had quietened down.

As we approached the main gates, a pretty girl wearing the standard-issue student uniform of jeans and T-shirt, and a pair of owlish glasses was just on her way out towards the car park, and on her chest I couldn’t help but notice that she carried a small badge which said: “vigilante”.

Now “vigilante” puts you in mind of all those lynch-mob scenes in B Westerns, but the Spanish word roughly translates into the English office of “caretaker”; “taking care”, I hasten to add, in the Disney sense of “looking after” as opposed to the Al Pacino type of “taking care” which usually results in a welter of bullet-ridden bodies. I suppose that makes “vigilante” sound quite civilised.

Anyway, the reason our owlish student was on her way out to the car park was to get a cigarette, but she promised she’d be back in a minute to show us round.

We explained to her that we were interested in the place because of its connection with THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE UGLY, and since this was one of our first days in Spain, I suddenly realised I didn’t know how to say the title in Spanish. I was okay with “good” and “bad”, but I didn’t know the word for ugly. I gave her the Italian title, then the English, and then tried “El Bueno, El Malo…” But she had already understood: “El Bueno, El Feo y El Malo”, she said, “ah si!” And then, cigarette in hand, she took us down the stone staircase to the lower level and across the ruined courtyard, now overgrown with weeds, and bearing the stunted remains of what must have once been enormous circular stone columns. At the far corner was a newly-built iron staircase that visited several levels of a square building that appeared to once house the monks’ cells, and at the top level, she took us down a ramp and into a room with new window frames and fresh plaster. Pointing through a window at the far right of the room, she said “here.”

We looked out across the forest of trees, their leaves bright in the sunlight, the river shimmering beyond, and high on the hill ahead of us was an old stone building, the “Ermita San Pelayo.”

This building matched the one seen through the hospital room that Blondie was occupying in the film, but Don was not convinced that this was the correct window, because the narrow corridor that Tuco walked along was further to our left. And despite our vigilante’s confidence that this was most certainly the window of Blondie’s room, we realised that we were standing instead in the room where Tuco meets his Franciscan brother, portrayed by Luigi Pistilli.

So we investigated further along to the left, where the corridor now began, and although everything is now in the process of being restored, we believe that the very first room in that corridor, which could also be accessed from a side door that opened into the larger room where the girl had first taken us, was the correct room for Blondie’s hospital bed:

A room originally belonging to the abbott.

After taking several photographs, we went up onto the roof for some excellent views of the surrounding countryside, and then back down to a large vaulted chamber on the ground floor that had every possibility of being the room that contained the wounded soldiers.

In all the rooms that were currently being renovated, there were faded images of old religious frescoes, and our vigilante explained that these were currently being re-painted by an artist from the Metropolitan Museum in New York, who was currently helping them with the restoration.

He was apparently due that afternoon, and the girl said that she wished we would come back and see him. As it turned out, we discovered something even more spectacular that afternoon, and sadly did not have time to return.

- Leaving the Monastery - Castillo de la Bateria, Rodalquilar, Almeria

When Tuco rides away from the monastery with the recuperated Blondie, their wagon takes the same road past the Castillo de la Bateria and the mound of rocks that Indio’s band ride past with the stolen safe from the bank at El Paso in FAFDM. Only this time, the road is traversed left to right, heading towards La Playaza, the Rodalquilar beach.

- The dusty Cavalry - Twin Peaks plain, Almeria

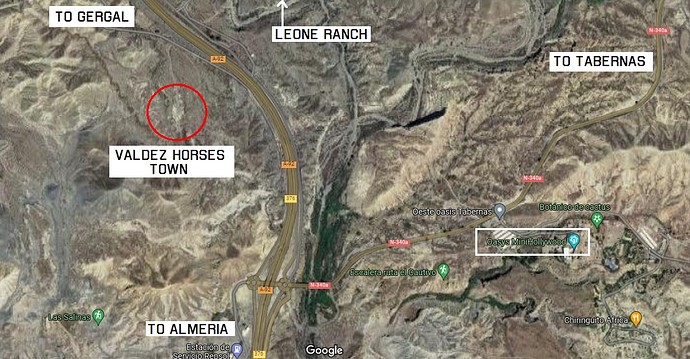

Following the N340 Almeria - Tabernas road for about 24 Kilometres from Almeria City, there is a left fork towards Gergal, designated the C3326. There was a lot of construction work going on here in year 2000, with old crumbling roads being replaced by sweeping new highways, but since the new and old roads follow more or less the same route, these directions should remain valid. Less than a kilometre from the fork, our first landmark is the “Rancho Leone” sign on the right-hand side, but we’re going to ignore that for now, and concentrate on finding a little dirt track to the left that takes you onto a grassy plain ringed by a horse-shoe of steep hills. Easily visible from the road, and accessed by this dirt track is a small, grey adobe village in a very bad state of repair, which was featured in the John Sturges Western THE VALDEZ HORSES/CHINO, starring Charles Bronson.

And this is all that’s left of it now - an imprint on the earth

According to Jose Enrique Martinez Moya in his book “Almeria, un Mundo de Pelicula”, the town, which he refers to as “El Poblado De La Carretera De Gergal; Poblado Nueva Frontera”, was built for the Don Chaffey movie CHARLEY ONE-EYE in 1972, but I believe that he is in error here. In the summer of 1972, I was undertaking my first exploration of the Spaghetti Western sites of Almeria, and can remember with absolute clarity that this adobe town did not exist at that time. However, I also remember that this particular area was liberally littered with the detritus of the CHARLEY ONE-EYE production: a sprinkling of many-coloured film cores, long twisted black ribbons of 35mm film, and discarded pages of the CHARLEY ONE-EYE script trapped in the enveloping branches of prickly bushes where the wind had blown them, and where the rain had first drenched them into a shapeless mass before the sun had baked them into cardboard.

This was a British Film crew, of course, and the fact that they were a bunch of litter louts, annoyed me greatly, but did not really surprise me at all: The British Empire was ever thus.

These relics of the production suggested that it had already upped-stakes and gone to the cutting rooms, so with no village in evidence at the time, I cannot believe that they then came back, built the village and shot some more.

When I returned to Almeria in 1974, the adobe village had been newly built. It consisted of a Mexican end featuring a tall church with a triptych of bell archways, and a Western end with a brightly painted saloon, general store and other typical buildings. It was not a large village, and in fact the buildings felt somewhat scaled down from the norm; they were far less grand, for instance, than those designed by Carlo Simi for El Paso.

Now, THE VALDEZ HORSES was made in 1973, and since this village does feature quite heavily in the movie I believe that it had been specifically built for this production.

You would probably not stay too long here today, since most of the buildings have collapsed, particularly the Western end whose wood has probably been cannibalised for other productions. The circular well contains slimy green foetid water and judging by the collection of plastic and glass bottles, food wrappers and other human detritus, has evidently seen regular use as a trash bin by those couldn’t-be-arsed tourists who leave a worse stain on Europe than Attila the Hun.

Leaving the village, the dirt track continues to the West to arrive at a narrow gap that cuts through the ring of hills. This terrain should be very familiar to Spaghetti Western aficionados; it’s where the stagecoach up-tips in FACE TO FACE, and where various riding and shooting scenes from films such as KILL THEM ALL AND COME BACK ALONE and A PROFESSIONAL GUN have been photographed.

The pass is to the right of the picture. I wanted to make sure you saw the Karst en Yesos sign, so you know you’ve missed the dirt track going up. But by using the sign, you can find it going back down.

Back in 1974, you could drive through this pass, but it has now been barricaded by a stone wall, and an iron gate with a hefty chained lock. Don was keen to try out his bolt-cutters again, but I refused to discuss the matter, slung my water flask over my back, my cameras round my neck and began to hike out onto the huge plain that now spread before me. In a movie, Don would draw a gun and yell at me to turn round, and I’d keep walking. In real life, I was just waiting to hear the ping of metal as the chain separated into two and smacked against the iron gate. A bullet might have been kinder.

Fortunately, Don left the bolt-cutters alone, and festooned with his own collection of cameras, binoculars, water bottles and the hugely important photo-file of screen-grabs, he trekked after me.

Almost as soon as you get out on the plain, you notice a conical hill on your left, and if you walk just beyond that, and then turn 90 degrees to the left, you will end up staring directly towards the area from which the dusty cavalry ride in GBU. Turning around and looking in the opposite direction, you can clearly see the hills that are behind Tuco and Blondie when they are driving the wagon up to the soldiers.

The track down which the wagon would have come is almost completely overgrown, and yet the whole area is criss-crossed with other tracks leaping off in all directions. There is also a large man-made mound of earth here that contains a small entrance, probably representing a mine-shaft. Neither of us remembered seeing it in any movie, and I was certainly not aware of its existence back in 1974.

Again, aficionados of Spaghetti Westerns will find much here that is recognisable, nothing more so than the twin-peaked hill that rises above the barren part of the plain directly ahead.

In 1972, there was a Waystation built here which had been used in Giorgio Capitani’s OGNUNO PER SE with Van Heflin, but now little is left other than a few bits of wood, and surprisingly a pair of solid cart wheels on an axle that had not moved position in the twenty-six years since I had last been there.

Prior to the construction of the Waystation, there had been another village here that appeared in DEATH RIDES A HORSE, where John Philip Law gets the traditional burying-up-to-his-neck-in-sand treatment. Jose Enrique Martinez Moya refers to the OGNUNO village as “El Rancho De Las Cercanias De Las Salinillas”, and the earlier DEATH RIDES A HORSE version as “El Poblado De Las Salinillas”.

The twin-peak mountain once carried a watchtower for the prison camp in KILL THEM ALL AND COME BACK ALONE, although the real camp was not built on the other side of the mountain as the film would have you believe. In Burt Kennedy’s DESERTER, it is beneath this hill that they test out the Gatling gun, and not quite in line, but slightly to one side is an outcrop with a derelict hut beneath it where the bullets were supposedly directed.

Stepping to the edge of the plateau, to which Tomas Milian climbed in THE BIG GUNDOWN, you get a splendid view down into the many ravines through which hundreds of cowboys must have galloped in as many Westerns, and remember that even the Legions of Rome have marched through here in the opening of Elizabeth Taylor’s CLEOPATRA.

The plateau also served as a landing zone for the helicopters of Mark Robson’s Algerian War movie THE LOST COMMAND, a fact that seemed about to be eerily repeated, because as we stood there enjoying the atmosphere of one of the most vivid of Spaghetti western locations, we couldn’t help but notice approaching us five black dots with noisy engines that soon formed themselves into military Helicopters.

They were a few minutes getting overhead, minutes in which we wondered whether they were coming in to land, and whether this was why access to the plateau had been barred, and minutes in which I felt very relieved that Don had not used his bolt-cutters after all. I don’t know what Don was thinking, but he’s sort of a cool guy, so he was probably wondering what make the Helicopters were. “That’s a Chinook, Mike”, he called over.

Although the location was spectacular, the wind got pretty fierce that day, and we were lashed with the sand that the wind kicked into our faces. Fortunately, if you go back to the Almeria-Tabernas fork, there’s a new garage that sells Military-style camouflaged floppy hats with chin-ties, and although they look pretty stupid when you put them on, they are an essential protection against the burning heat and the stinging wind. Which I guess goes to show that Leone’s concept of the dusty cavalry was a pretty authentic idea for this part of the world.

From the vantage point of this plateau, you can see another plateau almost directly ahead of you, but slightly to the right,

and in 1974 you would have had difficulty in avoiding seeing a large Western Fort that occupied such a commanding view over the Almerian ramblas. It’s not there anymore, but Don and I decided to go see if there were still any clues remaining as to its existence.

Now it looks like you should be able to take a short walk around twin peak mountain and get onto the plateau from there, but there’s a deep ravine in the way, so you have to return to the Almeria highway, and approach from that side. At the time there was a huge bridge under construction, but we had timed things nicely by visiting on a Saturday, so that there would be no construction crews there to tell us to go away. Of course, this also meant that if we got stuck in the soft sand of the river bed, there would be no-one there to help us out, and we very nearly did get stuck in a patch of very soft sand, which Don only just managed to avoid by keeping his speed up to what would otherwise have been considered lunatic levels.

We parked on a hard piece of the river bed, at just about the point where the Legions of Caesar were massed after the Battle of Philippi, in the opening sequence of CLEOPATRA, and then hiked up a steep track onto the plateau.

There was a large, flat grassy area here, that attracted the eye by being so visually unusual in this area of scrubland and which deceptively suggested that it may have originally held the foundations to the fort. But it was slightly further West where we found it’s remains, scattered amongst those gorse bushes that seemed to grow everywhere on these plateaus.

The fort had originally been built for Burt Kennedy’s THE DESERTER in 1969, and Senor Martinez Moya refers to it as “El Fuerte De La Rambla/Fuerte Gobi”,which suggest it had also been used for some Eastern movies as well as Westerns.

In 1972, the Fort was completely standing, and in good condition with Block-houses and towers, the Main Gate and a perimeter fence stretching on three sides. In 1974 it was being used for a BBC production of CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS, and I saw a crew of artisans at work decorating it for this particular production.

All the buildings were complete four-wall structures, and in the gloomy interior of the stable I found what at first glance appeared to be a dead horse, but on further inspection turned out to be a fake dead-horse, with bits of straw poking out between the stitched skins to prove the lie.

In year 2000, the fort appeared as if it had been stomped by a giant foot. Most of the wood and plasterwork was still there, but flattened to the ground, decaying and become ever-more brittle as the years of endless sunlight continued to bake it into dust. Only a small six-foot stretch of original palisade had been re-erected like a tombstone to mark this interesting location.

The tower was never an actual set at the Almeria location … it’s a matte painting or rather two paintings / foreground miniatures for the differing angles. The rest of the action continues in an Italian location, where there was a real tower and various buildings.

The same technique is used at the beginning of ‘Kill them all’ … to expand the northern army camp (lots of extra tents) and also add hills in the background of the shot.

I can believe that. The opening glass painting of “Kill Them All” was incredible. It’s actually used at the lower end of “White Rocks” near Colmenar Viejo from FAFDM.

The Italian location is also the prison camp in “And God Said to Cain”.

You were actually able to drive to the Valdez village and on to Salinillas!

The service road down into the valley towards the village is now blocked for cars as part of the service road has collapsed.

I was planning to visit the Salinillas/rambla Lanujar at some time but was going to walk from the southern side.

If you mean the “Valdez is Coming” village? Yes, you can approach it from El Paso. Quite a walk. Hill too steep for a car.

If you mean “Valdez Horses”, then yes you can drop down from the Repsol station to Las Salinas and walk the hills and ramblas. You should also be able to park on the opposite side of the road to the Valdez town on a dirt road towards what google maps calls “Western Leone” which is Jill’s ranch from OUATITW. Then you just dodge the traffic to cross over to the other side.

It would be great if you could go there and give us all an up-to-date report.

I know that the ‘Chino’ aka ‘Valdez Horses’ town had been completely flattened by 2013 … I visited the site in 2010 and there was still a fair amount to see.

Tragic, isn’t it? It was great when it was still standing.

-

The Prison Camp.

Don claimed to have found this near Carrazo where there was a field of cattle bones strewn around. I cannot confirm or deny. -

Tuco boards the Train - Lacalahorra Station, Guadix

Tuco boards the train at the real station of Lacalahorra in Granada province. Back then it was still operating as a station, but now with the introduction of higher speed trains, modern track, and less local stops, these little stations between Guadix and Almeria are just relics of the past.

- Tuco jumps the train - Lacalahorra branch line, Guadix

Tuco jumping the train, like virtually all train scenes in Leone’s movies, and in fact all train scenes in all other Spaghetti Westerns is shot on the branch line between Lacalahorra station and Lacalahorra village. Today, the line is broken before it reaches the main Almeria Guadix road.

- The Shattered Town - Colmenar Viejo, Madrid

I believe it was Cenk Kiral who first used the phrase “Shattered Town” to evocatively describe this crumbling location which, in the film, is being gradually destroyed before our eyes by the constant bombardment of distant artillery.

It is the same location as “White Rocks” from FAFDM, and is described in that section.

- The Bridge - Arlanza River, near San Pedro De Arlanza, Burgos

Our starting point for the trip to the Civil War Bridge is the Monastery of San Pedro De Arlanza, Burgos.

We knew we had arrived in the correct area because of the steep white cliffs defining the valley like a natural fortress wall. And as we drove East, away from the Monastery, our eyes were constantly darting from the cliffs, to our album of photographic stills, and then to the opposite side of the road, looking for a gently sloping open field, perhaps still stepped by the old trenches. The valley was filled with trees, which made it difficult to see the river clearly, and what we needed to find was an open space where the bridge could have been built.

We drove for several kilometres along the road, until the cliffs abruptly ended, and having found nothing of any value, we retraced our route back to the Monastery, turned round and started again.

Just around the first bend of the road as you leave the Monastery, there is a long straight stretch of road, with a little side track to the right, dropping down to the level of the river and into the thick forest. We pulled over here, and noted with certainty that the high white cliffs were closely matching what we had in the photographs. To the other side of the road was a steep grassy hill, covered in clumps of bushes, but here next to the river was just dense forest, no open spaces at all.

It just wasn’t coming together, and I was beginning to think that maybe what we were looking for was around the other side of the mountain.

Then Marla said: “You know, those trees are probably only about twenty years old”. And suddenly everything fell into place: Rule number two - a lot can happen in thirty years.

We were here. The hill was a lot steeper than it looked on the film, and the river was not all that wide, although we knew that Leone had constructed a dam to fill it out. The cliffs were lining up nicely, and if you stood very still and imagined the trees slowly fading away, you could just about picture where the bridge would be.

We walked down the track to the river side, negotiating our way through thick patches of undergrowth, forcing our way past the tangled branches of low-hanging trees, swatting away various hovering insects that came to inspect us, and taking carefully measured steps so as not to sink into the damp swampy mud that glistened around us. The area had definitely been underwater at some stage, but we were unable to find any remains of the bridge that might help us to pin down exactly where it was positioned.

Returning to the car, I determined that what we needed to do was climb the field on the opposite side of the road, and take up the position that Leone’s cameras had occupied for that first amazing revelation of the trenches. So, equipping myself with a handful of frame grabs, the video camera, stills camera, binoculars, and water flask, I climbed over the stone wall, and began the long hike up the ever-steepening hillside. Don and Marla followed, but I was so desperate to get up there, that I soon left them behind.

“Be careful of snakes, Mike”, yelled Don helpfully, which didn’t help me at all.

The grass at the bottom end of the field was thinly spread over rough soil, as though it had been seeded rather than a natural growth, and as I progressed upwards, I began to see undulations in the ground that suggested the position of trenches that had been dug and then filled in. The grass got taller and then I hit a barrier of thorn bushes that stretched laterally across the entire field, and which seemed to have been deliberately placed there to impede the passage of anyone foolish enough to have hiked this far.

However, being British, and made of fairly stern stuff, and since I was sensibly wearing thick long trousers, I plunged into the thorns and traced a weaving circuitous route through them. Looking back, I realised that Don and Marla, in their tourist garb of shorts and T-shirts, just were not going to make it this far.

The hill was getting steeper, and the thorn bushes more closely packed, and so I had to keep stopping and then retracing my steps back down the hill in order to avoid some of the thicker clumps, before I could find a way around them and resume my ascent.

At the top edge of the thorn barrier, the last obstacle was a steep earth wall, and having hauled myself to the top of it, I was able to turn round and enjoy the splendid vista of this beautiful valley, whilst I was catching my breath.

“Can you see anything up there, Mike?” Don yelled out.

“Oh yes,” I gasped to myself. “This is it!”

I climbed higher until I reached the tree line, and then positioned myself to match the black and white photograph I had been clutching of Eastwood and Wallach staring past the camera, with the trenches stepping down behind and below them towards the bridge in the valley bottom; a magnificent view that now spread out before me, resplendant in all it’s colourful and glorious reality.

However, it was unfortunately true that a lot had happened in thirty years. Because to get that shot exactly lined up, I was now faced with the problem that two large trees had spent all those intervening years growing up to their full height right in front of where I was going to put my camera.

To the Western edge of the treeline was a wide pathway cutting through the trees, where Blondie and Tuco had ridden in at the start of the shot that reveals the trenches, and I figured that if I followed this path it would eventually bring me out in the car park across from the Monastery. I wasn’t too keen to descend that field and negotiate the thorn barrier again, and it seemed to me that on a clearly marked path like this, it would take me no time at all to get to the Monastery. I called down to Don what my plan was, and gingerly set off on my way.

It was a lovely sunny afternoon, the path was wide and flat, and I was enjoying the leisurely stroll. I stopped occasionally to take photographs of the view, and noted that here and there were wooden steps going off up steeper parts of the hill, very like those seen in the trenches of the film, but probably built for the forest rangers whose watchtowers could occasionally be seen jutting above the taller trees.

The path continued for further than I had expected, and then it gradually began to loop back on itself and head straight up to the top of the hill, getting more steeper as it progressed. Each time I thought I had breasted the hill, there was another stretch beyond, and I now appeared to be going directly away from where I knew the Monastery to be. By now the sun had gone in, and a light drizzle had begun. The gear I was carrying with me seemed heavier than before, and I realised to my horror that during my exertions I had dropped some of the photographs that I had been carrying, in particular the one showing the wide shot of the trenches, whose camera position I had been so painstakingly trying to copy.

I was pretty certain that the path I was on would eventually reach the Monastery, but how far it would circle the hills before returning, I had no idea, so I decided to retrace my steps back to where the loop-back started, and head off West. I managed to find a decent path running along the edge of a field, and then a smaller one heading into the trees, but then this branched off in several directions, and I ended up taking the one that sooner or later petered out to nothing.

So here I was in Burgos, all alone in the middle of a forest, festooned with cameras, hot, tired and being rained on.

The only thing to do was light up a Toscana and enjoy the moment.

When I resumed my journey, I pressed on towards the West, my speed greatly reduced by the undulating ground and the bushes that I had to circle. Presently I stumbled across another path, and as it appeared to be going the same direction I intended to go, I joined it and picked up some speed. Another five minutes, and I was on a tall ridge, high above the Monastery, and carefully picking my way down through the light scattering of bushes to the car park below.

A few moments later, Don and Marla drove up, having spent most of the afternoon shuttling between the Monastery and the bridge location, just in case I’d got lost and decided to return down through the thorn barrier.

“Did you get a good view up there?” they asked.

By now I was out of breath, so I just smiled. Rather smugly, as I recall.

There is a path to the Northwest corner of the Monastery car park, sealed by an iron gate, which I believe loops around the hillside and joins onto the path that I followed from the field of the trenches. The path is wide enough for a vehicle, but on the stretch where I abandoned it, it gets very steep, and its undulating, rutted surface is littered with loose stones. I am sure that this is the route the film crew would have used to get their equipment in to the top of the hillside, but back then it would have been more passable. To the Eastern side of the car park is another path which appears to head straight towards the field of trenches, but which peters out well before it arrives, and does not make a connection anywhere with the other path.

If you want the view I had, then you really need some sturdy trousers and high boots to help you negotiate the thorn barrier, and be prepared for a long walk. I didn’t say it was easy.

Google supplied this current image

Not exactly a secret any more is it?

I remember this being discussed on the internet soon after we had visited. One guy claimed to have found a rusty Civil War bayonet along the river bank. Good for him.

(I’m taking a short break now. Back in a week)

I am not 100 % sure what you mean by "and in fact all train scenes in all other Spaghetti Westerns ".

I guess you, as an extremely experienced expert of locations in Leone SWs, also know that there are some SWs with trains from other railway lines in Spain.

The recently solved ESPERANZA mystery from Navajo Joe for example was shot at a small railway station south of Aranjuez, called Ontigola. There are at least 2-3 more such railway locations outside Granada and Almeria in SWs.

Nearly all, or most. I wrote that in 2004. I should have corrected it. Mi dispiace.

“All glory is fleeting”

And don’t forget the old track from Gor to Guadix which was used for a number of SW’s🤠

- The Sad Hill Cemetery - Contreras, Burgos

After we had been to the monastery of San Pedro de Arlanza, we resumed our journey east along the road we had been following. There were those white cliff-caps to the grassy slopes on our right, steep hills to our left surmounted with firs, and a winding river valley covered with a forest of tall trees. It was obvious that we were going to find the cemetery somewhere in this vicinity, because those white cliffs were so evidently similar to the ones seen in GBU, and which became such a spectacular backdrop to the showdown at Sad Hill.

After about 7 Kilometres, the road ends at a T junction with the town of Hortiguela on your left. We turned right to pass through Barbadillo Del Mercado and arrive at Salas De Los Infantes after another 7 Kilometres. Here we took the right turn, and continued to perform a clockwise route around the white-capped peaks. After 5 kilometres, we reached Hacinas, and then again took a right turn towards Carazo. At this point we were now at the very end of that long ridge of white cliffs. We were all convinced that these were the cliffs that were behind Sad Hill, and I felt sure that we just needed to circle around to the other side of them to see the cemetery.

As we sped along the road, I was looking for a turn to the right that would take us into the valley that had been revealed, because in the distance I was convinced I could now see a configuration of the cliff-tops that would match those behind the picture I had of Lee Van Cleef facing off Tuco and Blondie across the stone circle. But I was to be disappointed.

Carazo was another six kilometers, but in that six Kilometers I did not see any road off to the right other than a few insignificant fenced off cattle tracks. And then we were through Carazo, and looping around the end of a new ridge of mountains to travel through a deep switchback gorge hemmed in by spectacular craggy cliffs that would have been a most enjoyable sight had it not been for the fact that it had now become obvious to me that the Sad Hill valley was not accessible from Carazo.

The gorge flattened out just before Santo Domingo De Silos, a further 13 Kilometres from Carazo, and we stopped the car to climb a low wall and a grassy mound in order to look back. If the Sad Hill valley was innaccessible from the Carazo end, then maybe there was a way in from this end.

But we couldn’t see one from this end either.

I got Don to turn round and go through the gorge again so we could look over Carazo in more detail, but there were still no obvious routes into that valley. So we retraced our route back to San Pedro De Arlanza to explore any side roads from that end, and in so doing, found the location of the Civil War Bridge. I have already detailed this discovery in a previous section, but suffice to say, having found this location, we spent the rest of the day there, and had to resume our search for Sad Hill the next day.

Returning to Lerma in the morning, we took the lower road that passes South of the City and runs parallel to the Covarrubias road. It passes through Revilla Cabriada, Castillo De Solarana, Solarana, Nebreda, Quintanilla Del Coso, Santibanez Del Val and back to Santo Domingo De Silos, a distance of about 33 Kilometres. The latter town boasts some interesting historical sites, and as a result is a big tourist draw. The main streets of town are winding and narrow, but the outskirts are wide with large parking areas, usually filled with tour coaches. In the main square, I got Don to park opposite a lively bar, and went and grabbed the nearest waitress, a middle aged woman who would probably have remembered Leone filming near here.

I showed her the photographs, and she immediately remembered: Carazo!

This was hardly what I wanted to hear: we had already tried Carazo, and it wasn’t working. I went back to the car with a mixture of elation - the lady had confirmed Carazo; and desperation - we’d been there the day before, and found nothing.

I looked at Don, and said: “Carazo”.

He looked back at me: “Do we have to go through that damn gorge again?”

It turns out that I’d actually asked the wrong waitress. About nine months after we’d been here, there had been speculation on the Sergio Leone Web page about our trip, and where Sad Hill was located. Several people discussed the meaning of the vague description that Frayling had given in his book about the locations in Burgos, and an enterprising Englishman took his three kids down there in a Land Rover, stopped at Santo Domingo De Silos and asked a waitress in a bar about Sad Hill. She fetched out her son, who knew exactly where Sad Hill was, and he took them there. That enterprising Englishman was Howard Hughes, who is now pretty famous, having subsequently written many books about Italian Cinema.

So we passed through Don’s favourite gorge one more time, and once we had reached the end of the valley between the two mountain ridges at Carazo, we began exploring every little cattle track that turned off the road towards that valley. Some were fenced off almost immediately, others gave us enjoyably bouncy rides before they vanished into steep drops, or axle-wrecking boulders. Carazo itself looked deserted, but we tried a concrete path between two houses next to the horse-trough in the small village square, and after following it for a short while realised that we had found a route into the valley. The concrete soon gave way to dirt track, and we soon left the outlying houses behind as we gradually rose up the side of a small hill and towards the locked gate of a large farm sprawled on the hillside to our right.

At first we thought this would be the end of our journey, and the rest would be on foot, but as it turned out, I was going to be the only one doing the walking that day, and this little part of Spain was going to be etched on my memory for ever.

However, at this moment everything was fine, because at the farm gate a second track forked to the left, and although it was deeply rutted we managed to hang on until the road crested the hill and then dropped steeply into a gorge of white clay. This gave way to wide green fields and clumps of forest through which the track pressed inexorably onwards. To our right was a swampy pool of water which crept to the edge of our now muddy road, but we kept traction and progressed through the sunlit gap between the low trees into a small clearing. Beyond this, the track forked around a clump of trees before rejoining itself, and before anybody thought to suggest investigating why there were suddenly two routes, Don, who had been making sure to keep going so that we didn’t get stuck in any mud, took the right fork, found his wheels suddenly grabbed by the deepening ruts that he’d been following and jammed the underside of the car into a large mound of dried earth.

It was at this point that we realised why the track had split into two: there was the old route that was so deeply rutted that you got stuck, and there was the better route. Unfortunately Don had not chosen the better route.

We must have spent the better part of an hour jacking up the body to get it higher, digging beneath the wheels to jam stones under them, Marla and me pushing hard on the burning-hot bumper whilst Don gunned the engine in reverse and in all that time achieving nothing other than getting hotter, dirtier and more frustrated.

“Well, one of us is going to have to walk back”, says Don, looking at me.

“Yeah I know”, says I.

“Do you want me to come with you, Mike?” asks Marla.

“No, you’ll slow me down.”

It would have been a pleasant enough hike in normal circumstances. It was a couple of Kilometres back to Carazo, a cool morning with a cloudy sky, a magnificent place to be. I had a water flask with me, so I wasn’t going to be prey to the vultures, but I was worried about finding a garage open, a tow-truck or whatever, and persuading someone to help.

As it turned out, everything eventually fell into place. But at the time, the problems seemed insurmountable.

When I got level with the farm that we had passed earlier, I stopped and debated whether to go up to the house and see if anybody was in. There were tractors there and other farm equipment that could be used to drag our car from the ruts, but there didn’t seem to be anyone up there. It was nearer than Carazo, but Carazo held out more possibilities.

A little further along I met a middle-aged guy driving his car up to the farm, and flagged him down. I was aware that I was on a private road, so I apologised to him, flashed some stills from THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY, and told him that we were looking for the cemetery but had got stuck. His accent was a little difficult to follow, but he seemed to be saying that I was on the wrong road, and kept repeating Carretera Blanco - The White Road. I asked him if there was a telephone around here to call a garage, and he pointed back to Carazo, which is where I was going anyway. So I thanked him and resumed my journey.

As I reached the outskirts of town, I noticed some telephone wires above me, and tracked them around the tightly clustered buildings towards a big house with an open garden, fenced by the sort of high wire netting you get around tennis courts. And before I could stop myself I realised I was approaching the owner, an attractive forty-something lady peacefully stretched out on a lounger, sunning herself in a bikini.

I cannot remember whether she jumped up when I spoke, or whether the barking of the Rottweillers that she kept chained there disturbed her, but she quickly pulled a towel over her breasts and looked at me inquisitively.

“Lo siento, Senora, buscaremo por un telefono!” I gasped.

I knew she had a telephone, but I realised that the situation wasn’t too comfortable for either of us, since the barking dogs were probably going to bring out her husband, who obviously would have had a shotgun, so I turned and pointed towards the town and helpfully added: “Carazo - Hai un telefono?”

“Si, si” she agreed, and pointed towards town with a certain display of relief.

“Gracias!” I said, and backed briskly away; the cacophony of dog-barking ringing in my ears and refusing to subside until I had passed several more buildings and finally reached the centre of the village.

Here, I found a girl of about twenty who was busily hanging out her washing alongside the communal refuse bins, and since she was fully dressed, I felt I had a better chance of communicating with her.

“Lo siento senora, por favor, buscaremo por Sergio Leone” I cheerfully stated as I approached her across the empty road and held the GBU stills up for her to see.

Almost immediately she recognised “El Bueno, El Feo e Il Malo - Ah si”, she smiled, and pointed back towards the hills.

“Si”, I agreed “Detras!”. Behind there.

Having got the customer’s attention with the catalogue, I now had the problem of selling her the product.

"Un Problemo! Necesito un telefono.

El Coche… " and then I got stuck - just like the car.

I suddenly realised that I didn’t have the vocabulary to explain that our car was stuck in some ruts, and there I stood with my mouth open, mid-sentence, my brain turned to mush, and this pretty young girl staring at me, interested, intrigued and ready to help.

Fortunately my brain kicked back into gear, and I remembered that I had a notepad and pen with me, so I began to draw a picture of the car, and I drew some ruts. I drew a side-view and a front view. The front view showed the ruts better with the wheels buried in them, but the side view looked more like a car.

Then I drew a lorry with a crane on the back, and attached a hook to the car bumper.

All the while, the young girl was watching my sketching intently.

I drew some motion lines to show that the crane should start to move, and I drew an arrow to show where it was going, and I said “Arranca”, which I recollected meant you had to start the ignition.

Then I stepped back and mimed the car being pulled out of the ruts. And then I looked her in the eyes and waited.

Bless her, she had understood everything.

“Wait a moment”, she indicated, and disappeared around the side of the house to reappear a few moments later with a young man who was either her husband or boyfriend, I never did find out which. She explained everything to him, I showed him the sketch, and he smiled in recognition of the photographs: “Ah, El Bueno El Feo e El Malo!”

Then he pointed off to the left, swung his arm in a wide circle and said “La Carretera Blanco!”

There it was again - the mystical White Road.

“No, no”, I said, “we’re up this road, dos kilometros”.

“El coche is stuck in la terra. Necesito un telefono… un garaje…”

A garage? Yes, there was a garage he knew, in Salas De Los Infantes, and he knew where there was a telephone too.

So I followed him between the buildings, and as we came to the back of the houses, I glanced to the left and there was this big tractor parked there.

A tractor! That’s what we needed, I said to him. Forget the crane, can we get the tractor.

No no, he indicated - the owner was away or something - it was Saturday, not many people around. And anyway, the house with the telephone was just here, and he knocked on the door.

The place seemed deserted. It was now almost mid-day, and maybe they were already locked up enjoying a snooze.

We stood there for a couple of minutes, exchanging anxious glances. Well, I was anxious, he was more puzzled. So he banged on the door again.

A couple of minutes later, an ancient lady came to the door. She eyed me suspiciously for a moment, and then she recognised the young guy, and he started to explain who I was and how I’d got my car stuck, and needed a garage and asked if we could borrow the phone.

Well, of course we could borrow the phone. Would you like the phone-directory? Please come in. She was so very helpful.

Pretty soon they’d found the right place in the phone-book, and she was ringing the number for him, and he turns to me and asks me what make of car I’ve got.

What make of car? How the f*** should I know, I’m the frigging navigator, not the driver.

It’s red.

Wait, wait, it was coming to me.

A Renault, I think. Yeah a Renault. No maybe it’s a Citroen…

Wait a minute, why does he want to know the make of the car?

Then it struck me; he thinks the car is broken. He thinks the engine needs fixing.

No No, I tell him, the engine is fine, it does the “arranca” part just fine. We’re stuck, we need pulling with a crane or a tractor.

“He needs a tractor”, says the old lady. And then they start gabbling twenty-to the-dozen, and I can’t follow a word of what’s going on, but then the young guy is coming out and we’re saying goodbye to the old lady, and going back round the house to where the young girl is still waiting for us. Now the guy starts talking to her at high speed, and then she brings him over and they look at my sketches of the car and the crane, and it’s gradually coming out that there are a few words of English that she knows, but doesn’t really like to say in case I make fun of her accent, and we establish that the car engine is working just dandy; it’s not broken and we just need pulling out.

Whilst all this has been going on, another attractive middle-aged lady, who has been standing outside her house door beating a carpet, calls out to the girl to ask her what’s going on. More fast Spanish ensues between them, and then all three of us are crossing the road to talk to her about our little problem

The girl shows the lady my GBU stills, and she smiles in recognition, and everybody repeats the name of the film, and we’re all laughing happily, and then they start talking fast again. I didn’t recognise much of what was said, but I’ll swear the Carretera Blanco came up again, particularly as they were all sweeping their arms off to the left in unison.

Then the lady takes a look at my drawings, and it’s all very clear to her now.

How far away is the car, she asks.

“Dos Kilometros”, I make a guess at two kilometres.

Oh, that’s fine, no problem she says, and she waves her arms around to indicate that the four of us will walk all the way out there to the car and push it out of the rut. And she’s indicating pushing with her hands as she says it. She made it look so easy I damn near went along with it, and then reality pervaded my brain, and I said no, no, it’s very deep, we need a crane…

“You need a tractor!” she says.

Before I know what’s happening, the guy sets off back behind the houses again, and reappears a moment later driving his car off down the road towards the general direction of where the legendary Carretera Blanca turns out to be. The lady tells the girl to keep her informed, and then goes back to her house, and me and the young girl wander back to her washing.

“Wait here a moment”, she says, and disappears around the side of the house.

Now I’m all alone in a deserted village, on a quiet Saturday in the middle of Sergio Leone country. And I’m wondering just when I’ll waken up.

The girl returns a few moments later with a lighted cigarette in her hand, and smiles at me, sheepishly.

I smile back, and reach into my pocket for a Toscana. Then we stand there in the shade of the buildings, and smoke. You can always find a friend if you smoke.

The boyfriend, or husband, whatever he was, returned after about ten minutes, and he brought with him this handsome young guy in his thirties, who got right out of the car, waved a brisk hello to everybody, and then went straight behind the buildings.

Almost immediately there was the roar of some massive engine, and I’m almost sure I could hear a triumphant fanfare on the soundtrack as this big tractor lurched into view. It was the tractor I had spotted earlier, and these wonderful people had figured out where the owner was and fetched him.

The driver indicated that I was to get up into the cab, which was small and cramped and not designed for other than the one occupant; and so I found myself standing, with shoulders hunched over from the low roof, pressed up against this guy to whom I’d hardly been introduced. And thus ensconced, we traversed the two bumpy kilometes all the way along that hump-backed dirt track to haul our car out of it’s rut.

To be continued…