While everybody’s busy following the European Football Championship, I unflaggingly dedicate my precious time to scientific research in the burgeoning field of Spaghetti Western studies. Here are some (rambling) thoughts on Una colt in pugno al diavolo.

Already its opening sequence insults the viewers’ temporal and spatial understanding of moving pictures (shaped by cinematic conventions, of course). A wagon train is rolling through a barren desert landscape, from the left side of the frame to the right. The first cut directs the viewers’ attention up a cliff, from which seven armed riders look down. According to conventional camera movement, positioning, and cutting, the riders would watch the wagons from the trek’s left side. The wagons turn around, reverse direction, and now are moving from the frame’s right side to its left. Where are the armed riders, left or right? Next cut: the wagons are still moving from right to left. Cut: a look down at the trek from the viewpoint of the presumptive bandits; it moves from the right side to the left side, and the armed riders are again to its left side. Something’s wrong: either the first shot of the bandits was spatially (or temporally) misplaced, or they have changed their position and moved from one side of the ‘canyon’ to the other. The camera zooms in on the mounted bandits: they still are clearly on top of a cliff, the only background blue sky.

The bandits start firing but – irritatingly – straight, not down, as would be expected.

Next cut: where are they now? How did they get down so fast?

Cut to close-ups of the bandits’ revolvers: verdure in the back.

“Sculpting out of time” and just one of many instances of bad editing in Una colt in pugno al diavolo. The next one occurs right after the title sequence: again, the temporal and spatial coherence of consecutive shots is neglected, as the sheriff leaves his room and presumably ‘zaps’ down the main street to a horse with a dying rider on its back. Even an approaching man and woman in the background are out of time and space from cut to cut.

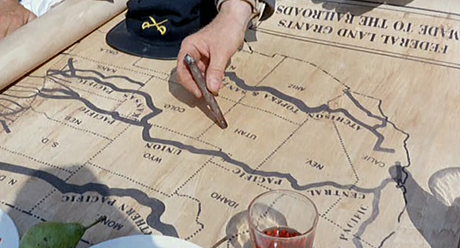

Mounted across the main street, a huge banner greets viewers and visitors: “Welcome to Las Vegas.” Why did the makers of Una colt … choose this town? Las Vegas was founded as a city in 1905. At the time of the film’s temporal setting, it wasn’t much more than an abandoned fort. Nevada gained statehood at the end of the Civil War, during which it was mainly pro-Union. Sergio Bergonzelli has Confederate troops stationed in Nevada. In their first scene, the commanding officers – who wear uniforms that look like leftovers from a WW I movie – study a map showing “Federal Land Grants Made to the Railroads” and railroad lines completed years after the movie’s time frame.

“Death Valley he called it. Well, I suppose one name’s as good as another.” Again, a strange decision by the movie’s makers: Death Valley’s dislocation from California to Utah. Of course, Westerns, and in particular Italian Westerns, shouldn’t be judged in terms of historical or geographical verisimilitude. Nevertheless, a certain degree of semblance or plausibility is required to obtain the viewers’ willingness to involve themselves into a (conventional mainstream) movie’s narrative (cf. Coleridge’s suspension of disbelief).

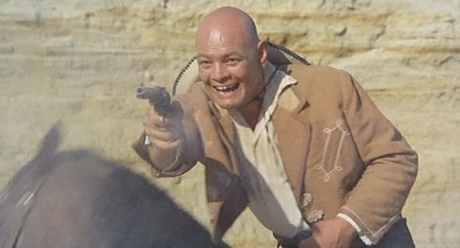

I tried to like Una colt … but failed. I think its cinematic craftsmanship leaves too much to be desired to take the film seriously. It suffers from sloppy editing, careless production design and ill-founded historical and geographical setting; not to mention thespian ineptitude, ranging from clumsiness (Bob Henry, Lucretia Love) to histrionics (George Wang, Marisa Solinas).