–

– –

– –

– –

– –

–

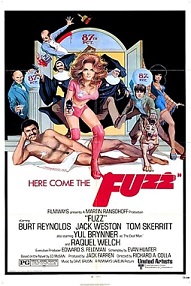

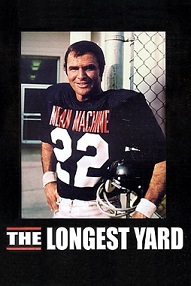

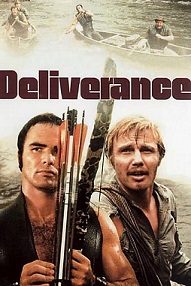

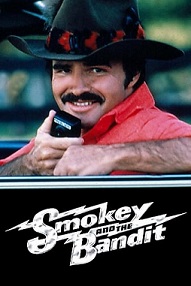

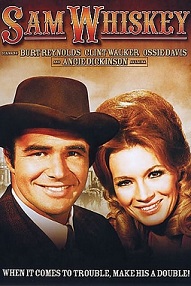

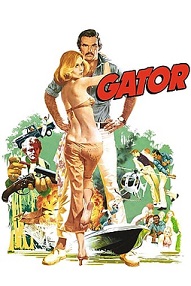

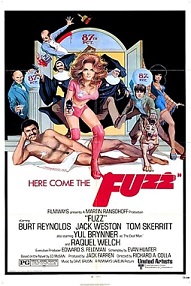

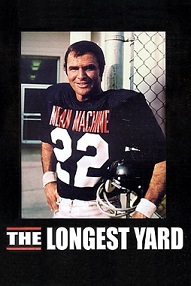

R.I.P.!..Burt Reynolds.

–

– –

– –

– –

– –

–

R.I.P.!..Burt Reynolds.

Last ten days:

Star Trek: Into Darkness (Abrams, 2013)

Star Trek: Beyond (Lin, 2016)

The Cabin in the Woods (Goddard, 2012)

The Endless (Benson/Moorhead, 2018)

The LEGO Batman Movie (McKay, 2017)

The Wolverine (Mangold, 2013)

Brimstone (Koolhoven, 2017)

Django Unchained (Tarantino, 2012)

Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa (Lowney, 2013)

Locke (Knight, 2013)

The Cannonball Run (Needham, 1981)

Deliverance (Boorman, 1972)

Killer Joe (Friedkin, 2011)

The Grey (Carnahan, 2012)

Star Wars: The Last Jedi (Johnson, 2017)

Rise of the Planet of the Apes (Wyatt, 2011)

Upgrade (Whannell, 2018)

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (Reeves, 2014)

War For the Planet of the Apes (Reeves, 2017)

The Purge: Anarchy (DeMonaco, 2014)

American Sniper (Eastwood, 2014)

I watched Enigma with Martin Sheen. Sounded interesting, started off well but very quickly became a one star film that couldn’t manage to redeem itself.

Not really a movie but we (Mrs Fudd and myself  ) watched the first season of The Bridge (Bron (Swedish) or Broen (Danish)). It kept us close to the telly for a couple of days.

) watched the first season of The Bridge (Bron (Swedish) or Broen (Danish)). It kept us close to the telly for a couple of days.

Now it’s about time for another western.

I watched Army of Darkness Director’s Cut on the new blu-ray steelbook I got recently. I also watched the feature-length Making Of documentary that was made for the release. Needed a break from the constant spaghetti western marathon plus reading Alex Cox’s book.

Return of the Living Dead - 4.5/5

Such a fun movie. I still haven’t bothered to watch the sequels, but I’ve heard they suck.

I have this release aswell as the Koch 6 disc edition. It’s a close call as to which version is better.

PS. I guarantee Sam Raimi saw the Stranger movies. Especially Get Mean.

This Scream Factory release has the US Theatrical Cut, the Director’s Cut, and the International Cut on 3 discs.

There’s no question there’s a lot of parallels between Get Mean and Army of Darkness.

So does the Koch version, and almost identical extras.

The character of Ash morphs into a slapstick victim throughout the series, just like The Stranger did.

I think it would be interesting if Bruce Campbell and Tony Anthony made a movie together ![]() I’m sure they’re aware of each other. Maybe a cameo of Tony on Ash vs. Evil Dead as Ash’s father or uncle? In any event it would have to involve a 4-barrel shotgun at some point.

I’m sure they’re aware of each other. Maybe a cameo of Tony on Ash vs. Evil Dead as Ash’s father or uncle? In any event it would have to involve a 4-barrel shotgun at some point.

Battle of the boomsticks!

I always knew Get Mean was highly influential movie. ![]()

Last 12 days:

Prometheus (Scott, 2012)

Alien: Covenant (Scott, 2017)

Batman: Year One (Montgomery/Liu, 2011)

Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (Snyder, 2016)

The Reef (Traucki, 2010)

47 Metres Down (Roberts, 2017)

Skyscraper (Thurber, 2018)

Paranormal Activity 3 (Joost/Schulman, 2011)

Paranormal Activity: The Marked Ones (Landon, 2014)

Detroit (Bigelow, 2017)

Black Panther (Coogler, 2018)

Mission: Impossible - Fallout (McQuarrie, 2018)

Slow West (Maclean, 2015)

The Homesman (Jones, 2014)

Attack the Block (Cornish, 2011)

This is the End (Rogen/Goldberg, 2013)

The Big Boss (Wei, 1971)

Tyrannosaur (Considine, 2011)

V/H/S (Wingard/Bruckner/West/McQuaid/Swanberg/Radio Silence, 2012)

The Good Dinosaur (Sohn, 2015)

Cars 3 (Fee, 2017)

Killer Constable (Kwei, 1980)

Captain America: The First Avenger (Johnston, 2011)

Dredd (Travis, 2012)

Under the Skin (Glazer, 2013)

Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau (Gregory, 2014)

The Neon Demon (Refn, 2016)

Green Room (Saulnier, 2015)

Smokey and the Bandit (Needham, 1977)

Blue Ruin (Saulnier, 2013)

I’ll need to re-watch this. “The best shark movie since Jaws” was a very ballsy statement.

I think every bloody shark movie since Jaws makes the same claim, don’t they? ![]()

The Reef is one of the few genuinely good’uns though, imho.

A Town of Love and Hope (1959) - Director: Nagisa Oshima - 7/10 - Oshima’s debut is surprisingly mature in form and substance. The movie basically showcases most of thematic motifs he would expand on later down the road. The film recounts a story of a young boy, Masao, coming from a destitute family which barely makes ends meet. His mother works as a shoeshine, but it doesn’t really amount to anything, so Masao resolves to start selling pigeons which escape from their new proprietors after several days and then return to Masao who then resells them. Masao meets a bourgeois girl, Kyoko, who takes interest in the boy and endeavors to help him sort himself out and empower him to lift his family out of poverty by pressurizing her father, who is an industrial mogul, to hire the youngster in his factory.

Problems arise when Masao’s fraudulent past comes to light which in turn prompts the recruitment committee at the factory to reject his application. Once Kyoko finds out that Masao repeatedly sold pigeons and scammed his clients, she turns her back on him and even goes as far as buying Masao’s pigeons (again) and ordering her brother to shoot them with a rifle. Oshima films the entire affair in a stark monochrome palette, opting for a very gritty, grungy look that accentuates Masao’s strong sense of alienation. Nevertheless, the point is not to render the motion picture maudlin or particularly schmaltzy, it is to emphasize the fatalism of Masao’s situation and the eagerness of the society at large to dismiss him as a dysfunctional individual on account of his involvement in the previously described fraud.

Despite the fact that Masao was forced to hoodwink his buyers owing to his poor economic condition, Kyoko’s father is not willing to give the youth another chance which only reaffirms Masao’s social status and indurates the minor who then vows to carry on with his fraud scheme. Oshima stresses that the reason why Masao dupes his clients is not because he is especially dysfunctional as a citizen or particularly hellbent on obtaining cash via deceit, but because he has been coerced into such position by the remainder of the society which is still very conspicuously delimited by class consciousness. He doesn’t have much say in it - he is one of paupers and is destined to remain one.

Cruel Story of Youth (1960) - Director: Nagisa Oshima - 9/10 - Definitely one of the most important Japanese films of all time and a milestone in the modern Japanese filmmaking. The film portrays the story of a young couple who decides to rob elderlies keen on harassing young women roaming the streets. Oshima here takes a shot at humanist school of filmmaking represented by Kinoshita, Kurosawa and Kobayashi. Oshima regarded their approach to cinema and shaping characters as excessively defeatist in the sense that their motion pictures overwhelmingly relied on sentimentalism as well as victimization in order to elicit emotional response which in turn camouflaged the very nature of oppression some of these films wanted to portray.

Oshima likewise draws parallels between the victimhood culture somewhat espoused by humanism and the defensive quality of anti-war demonstrations in the 1960s. Cruel Story of Youth also constitutes a criticism of the old Left of the 1950s which could not shape its political fervor into concrete political actions by virtue of the fact the political agenda was too exorbitantly dependent on victimhood and consequently, the mentality of the anti-establishment faction was still firmly grounded in pre-modern, feudal framework and this is why the struggle subsequently petered out and the society began to stagnate. This movie is basically an allegory of all this disillusion with postwar Japan, except that Oshima does not touch upon the Anpo protests directly (demonstrations against the renewal of the Japan-US military treaty) and primarily focuses on forming his characters and expressing the abovementioned issues through two main leads. He refuses to portray the central hero or the heroine as straightforward victims and chooses to turn them into as much of victims as aggressors whereby he intends to highlight their subjectivity, confronting the humanist ethos and declining to succumb to the culture of victimhood blaming militarism, imperialism etc. for all calamities that the Japanese society had to experience and endure in the wake of WWII.

Simultaneously, he punctuates the nihilism and the lack of purpose discernible in the youth of the 1960s. Again, the absence of morals is definitely not remedied by the older generation which seeks to exploit the youth basically at every turn. Both central figures prostitute themselves and are practically abandoned by their families which is stressed even more by the visual marginalization of filmed environments, which is also a direct fulmination of classical Japanese filmmaking of Ozu or Mizoguchi. It’s one of the most anti-sentimentalist films I’ve ever seen which is probably why it’s so good.

One-Way Ticket to Love (1960) - Director: Masahiro Shinoda - 7/10 - Shinoda’s debut is an overall satisfying venture dealing with the exploitation of stars in the Japanese entertainment industry. While the primary focus of the motion picture is the issue of ill-treatment of the youth by the older generation, the movie generally has a more sentimental flavor to it and isn’t quite as grim as Oshima’s works. It can be partly chalked up to the fact that Shinoda never was as fervently radical as Oshima or even Yoshida for that matter. Despite the fact that his efforts fulminated against the Japanese establishment, his filmmaking was usually more subdued in terms of structural or formal experimentation. It’s a minor effort, but still worth a look, even if its denouement leaves a lot to be desired.

Pale Flower (1964) - Director: Masahiro Shinoda - 10/10 - A re-watch - Probably the best yakuza-eiga ever made and a masterpiece. The story revolves around a yakuza, whose only way of deriving pleasure from his day-to-day existence is by gambling or resorting to violence, and his relationship with a mysterious female who is likewise a gambler keen on perilous thrills of the underworld. The monochromatic, chiaroscuro cinematography is delightful to behold and the grim atmosphere readily reminds one of Melville’s style, but the venture at hand is probably even more nihilistic. As a matter of fact, it was deemed morose and morbid insofar as one of the biggest Japanese studios Shochiku refused to distribute it by virtue of its exceedingly lugubrious nature.

Pigs and Battleships (1961) - Director: Shohei Imamura - 8/10 - A re-watch - I liked this one a lot more this time around. Imamura has a very particular touch to his movies, so singular it’s kind of hard to clarify. I guess you could say it’s darkly humorous, but not in the way that ridicules its central characters and instead, it primarily endeavors to capture the absurdity of the mundane and quotidian events. The film analyzes the issue of the US occupation of Japan and the impact it exerted upon the local population. The presence of US soldiers isn’t as much criticized here as it is primarily a form of personification of the foreign capital which strips people of their dignity and turns them into money-hoarding hypocrites willing to do anything for an appropriate sum of money. The only person declining to succumb to the corrupting influence of her environment is Haruko who ultimately proves to be the only person capable of escaping the debasing clutches of her village located adjacent to an American military base. She also serves as a sort of priestess figure guarding the spirit of the past. Her persona epitomizes the vitality and strength of the Japanese people for the most part. Imamura mostly sees vigor and true spirit of the Japanese in his rustic heroines who endure all kinds of oppression or humiliation and ultimately persist in their quest for survival.

Dry Lake (1960) - Director: Masahiro Shinoda - 6/10 - A re-watch - A decent entry from Shinoda. The movie is more notable for the topics it depicts rather than its intrinsic value or artistic splendor. That is not to say that there are no signs of Shinoda’s subsequent artistry, for there are lots of stylistic flourishes which would go on to define his later career. The problem is that the film treats its subject matter rather perfunctorily without providing much insight into analyzed issues or sufficiently interesting characters for that matter. While A Town of Love and Hope lasting over an hour felt incredibly efficient in the way it presented its tale without sacrificing the depth of its characters or the story, Dry Lake alludes to an array of themes without really delving into them all that much. Shinoda’s motion picture does raise some interesting points with respect to the nature of progressively radicalizing leftist groups growing increasingly similar to its right-wing counterparts and their fascination with violence for the sake of it instead of actually seeking viable methods of bringing about social or institutional change, but this alone cannot make for an adequately gripping viewing without supplying an adequate dramatic foundation.

A Flame at the Pier (1962) - Director: Masahiro Shinoda - 8/10 - A re-watch - Shinoda himself describes this work as his first venture he was truly satisfied with despite it being somewhat kitschy. Yeah, it is kitschy, but I like it a lot nonetheless. Shinoda casts a pop rock singer in the role of a yakuza who is hired by a corporate management to quench any signs of rebellion amongst dock workers endeavoring to form a union so that they can face institutional oppression and force the administration to improve their working conditions. At one point, the protagonist attempts to intimidate one of workers’ leaders at the administration’s behest, but accidentally slays the male who subsequently proves to be his beloved one’s father. The event makes him realize that he is, in fact, a lackey of the corporation with no real autonomy. The motion picture is interesting because of its depiction of how Japanese corporations used to deploy ruffians to disband labor unions which provoked a heated public debate in Japan at the time of the film’s release.

The Sun’s Burial (1960) - Director: Nagisa Oshima - 7/10 - A re-watch - A very grim feature film about the fate of those forced to inhabit Kamagasaki slums located nearby Osaka. The slums were erected because of Emperor’s decree that all paupers would be accumulated there so that he could avoid seeing them while on his way to Hiroshima port and then to Russia. The action of the pic is completely immersed in the reality of the destitute environment, offering a potent depiction of how individuals find different ways of rationalizing their existence while simultaneously being at the mercy of the collective embodied here by several yakuza gangs roaming the streets of Kamagasaki.

Some people dream about restoring the national glory of the Japanese empire; others feel bound by yakuza moral code despite the fact that their groups can betray and forsake them at any instant. The central heroine, just like Haruko in Imamura’s Pigs and Battleships, is intent on staying alive; she doesn’t care about mendacious sense of collectivism espoused by her neighbors which ultimately isn’t centered on its members’ well-being. The double standards shown here are also an allegory of the state – a citizen is supposed to abide by the state laws nonetheless the fact that the state in question may very well abandon the individual on a whim. The film isn’t as enjoyable as it’s predecessor, but it’s characterized by Oshima’s keen sense of aesthetics which incessantly manifests itself in the way it emphasizes the sun symbology directly linked with Japanese flag and iconography.

Good-for-Nothing (1960) - Director: Yoshishige Yoshida - 7/10 - A re-watch - Probably one of the most stylish Japanese New Wave movies that has ever been released. The film has a very chic look and a classy, jazzy soundtrack that adds to the charm. There is something about the way in which Yoshida cuts the entirety of the material that is just striking and there is something kind of consciously careless in the montage and filming process. The motion picture is primarily preoccupied with the issue of the youth’s waywardness and the lack of existential purpose which then propels youngsters to seek thrills in decadence and amoral conduct.

Blood Is Dry (1960) - Director: Yoshishige Yoshida - 6/10 - A re-watch - A pungent social satire about a man who attempts to commit suicide at the realization that his insurance company is about to make him redundant. This event is then used by the corporation to push an advertising campaign designed to maximize profits and improve the public image of the firm. While the material at hand does attest to the kind of social critique Yoshida would subsequently expand on, Blood Is Dry doesn’t have the same stylistic beauty which could potentially make it a bit more engaging. The narrative is a bit on the cut-and-dry side too.

Bitter End of a Sweet Night (1961) - Director: Yoshishige Yoshida - 6/10 - Very similar to its predecessor. The flick portrays the way in which the Japanese youth prostitutes itself in order to climb up the social ladder. Yoshida is quite critical of the kind of cutthroat mentality that pervaded the Japanese society at the time. The movie is clearly a manifestation of that as well as his view that youth is a rather destructive force.

Akitsu Springs (1962) - Director: Yoshishige Yoshida - 8/10 - One of Yoshida best efforts, even if it feels somewhat unusually dramatic for him. Albeit definitely very melodramatic and by the same token, very different from his usual filmmaking style that relies on cold, almost surgical precision and a methodical, detached observation of reality, his effort here boasts a rare sense of beauty somewhat reminiscent of Kinoshita or Ozu and works on a more conventional level. This is actually where Yoshida’s cinema does bear some resemblance to Antonioni to whom he’s been often compared throughout his career. The comparison is rather ridiculous once one takes into consideration Yoshida’s usual fashion of structuring his characters or narratives, which is exceptionally avantgarde, but here the narration is fairly contemplative which is why he’s stylistically closer to what Antonioni’s movies feels like.

Although it is shaped in a rather formulaic manner, Yoshida manages to infuse the material with his kind of social critique; the central heroine, Shinko, works in a thermal spring during the war. She meets Shusaku, a sickly young man, who falls ill while at the facility and then is brought back to health by Shinko. The female falls in love with him. She sees him change as years pass by and as he gradually relinquishes most of principles he used to believe in. He transforms from a poetic, idealistic writer into a cynical, corporate white-collar worker. Shinko, on the other hand, is a priestess of the past, she embodies the spirituality of the yesteryear and finds it difficult to integrate with the rest of the society. By the end of the motion picture, she barely recognizes the environment around her and fails to understand the calculated, impersonal philistinism Shusaku gradually begins to represent with his brusque demeanor. Last but not least, the cinematography is of utmost excellence and exhibits the kind of obsessive attention to every frame Yoshida would later become famous for, especially in case of his later works, where he would deconstruct, breach framing rules in lieu of trying to enshrine the center of composition.

18 Roughs (1963) - Director: Yoshishige Yoshida - 5/10 - Probably Yoshida’s most anti-humanist effort. I cannot quite pinpoint what it is that I find not all that palatable about it other than it is not all that engaging. The social commentary is very similar to what Oshima explored in A Town of Love and Hope which is why I won’t bother with particularly dissecting it here. The main character is supposed to take care of a group of 18 ruffians who are to work at the docks. The young thugs come from underprivileged backgrounds and have a proclivity for venting their frustration by resorting to violence. They refuse to defer to the ethics and morals espoused by the rest of the society, since the society in question ostracized them, relegating them to the position of ‘the other’ in relation to which the upstanding citizens can then define their moral code and delimitate social transgressions. Or something along those lines.

Escape from Japan (1964) - Director: Yoshishige Yoshida - 7/10 – A very atypical yakuza-eiga that manages to create an exceedingly somber atmosphere, quite unlike other yakuza movies I’ve seen. A bunch of individuals: a masseuse, a drug addict, a ruffian and a yakuza plan a robbery of a Turkish bath where the massager works. Everything goes wrong though. The film is an allegory of running from the rest of the society basically. After this film, Yoshida left Shochiku and embarked on an independent line of work.

The Insect Woman (1963) - Director: Shohei Imamura - 8/10 - A re-watch - Imamura’s film primarily concentrates on the evolution of the Japanese society which is observed through the prism of Japanese rustic femininity embodying the true Japanese spirit and stuff. Just like Pigs and Battleships, the motion picture displays an unusual sense of irony and dark comedy that makes watching it much more engaging and paradoxically thought provoking. Instead of caving in to sentimentality and dramatism, which is an obvious way of generating interest, it takes a different approach altogether, bringing forth the absurd inextricably intermingled with the mundane and exposing the irrationality still remaining dormant within the heart of Japanese society. Another thing that sets this apart from other movies of this kind (a Japanese subgenre called feminisuto and most prominently represented by Mizoguchi), is the treatment of the central heroine: she isn’t a victim Mizoguchi would probably want to portray her as. She is a victim as well as a victimizer – she doesn’t give a damn about the rest of society which strives to exploit her at every turn and seeks to ensure her own bodily safety and financial security. I found it extremely entertaining and refreshing. There is something very droll about Imamura’s filmmaking that I like.

I need a coffee.

She and He (1963) - Director: Susumu Hani - 8/10 - I must see more movies by Hani. His documentarian sensibilities tinge his films with a particular flavor similar to that of Teshigahara who also had a documentarian background. One of the most poignant movies I’ve seen in a while and a hidden gem. Its attention to detail as well as its accurate depiction of characters’ emotions are probably the reasons why it’s so good. Hani recounts the story of a young female who feels obliged to assist everybody around her, including those outside of her immediate community. Along with her husband, she inhabits a modern block of flats aimed at middle class citizens. On account of its being fairly recently constructed, the estate temporarily adjoins a shantytown. The woman befriends one of ragpickers living nearby who turns out to be her husband’s acquaintance from his university period. She attempts to lift him from poverty, but the ragman is not particularly eager to mend his ways. The movie primarily touches upon the formation of one’s subjectivity – by undertaking the social action, the wife asserts her identity and reduces the extent to which she is dependent on her husband.

A Story Written with Water (1965) - Director: Yoshishige Yoshida - 7/10 - The first independent production directed by Yoshida is a radical shift from the mainstream mode of filmmaking. The work is a dense, convoluted film filled with a warped sense of time and space which serves as a diegetic tool to emphasize the irrational, experiential nature of perceiving time. A Story Written with Water revolves around a man who is about to get married, but he has second thoughts about it. The movie by and large deals with the topic of mother-son incest and there are some subtle indications in regard to this throughout the entirety of the motion picture, nothing explicit though. The relationship of the protagonist and his mother is explored through a series of flashbacks as well as the examination of the so-called ‘unrealized past’ as well as dreams, rejecting the conventional chronology and adopting a form of acausal narrativization transcending the usual realist framework.

Part of this approach stems from the assumption on the part of New Wave filmmakers that the reality is a sort of multilayered matrix of different fields and spheres which interact with one another and cannot be adequately reproduced in realist terms. This radicalization of the narrative also derived from the fact that traditional Japanese cinema was formally already somewhat modernist: you can discern time ellipses as well as traits of episodic storytelling in Ozu’s works for instance which is indicative of transcendentalism in classical Japanese filmmaking. Hence, directors like Yoshida had to push things even further in order to distance themselves from masters of classical Japanese cinema as well as arrive at a new form of cinematic language. Likewise, Yoshida simply believes that time needs to be depicted outside of the usual causal conditions of realist storytelling. Now that we got that tedious shit cleared up (and assuming somebody actually intends to read all this shit), the film itself is very evocative and remains probably one of the best Yoshida efforts in experimental storytelling. It never strays into avantgarde phantasmagoria too far and doesn’t render its characters excessively alienating, whereby I mean too many personas saying weird shit for no apparent reason. It’s all fairly nuanced, well-balanced or well-seasoned, so to speak.

The Affair (1967) - Director: Yoshishige Yoshida - 6/10 - It is the first of several feminisuto flicks made by Yoshida. It’s okay I guess and the stylization at hand isn’t as bothersome as in some of his subsequent ventures. The characters, however, do function as symbolic cogs in a larger scheme of things revolving around female emotionality. The heroine basically flirts with three men concurrently: she is married to her husband for financial security, she sleeps with a blue-collar worker in order to appease her sexual needs and she flirts with a sculptor so that she can form an emotional bond with somebody. Therefore, according to Yoshida, female life is divided into three separate categories: financial, sexual and emotional. In the end, she chooses the emotional sphere i.e. the sculptor, even though he is incapable of sexually satisfying her on account of being paralyzed as a result of an accident. As I say, it’s all fairly formal in its execution, therefore don’t expect any sweeping drama or a gripping character study here, all personas here operate as a form of elucidation of the abovementioned argumentation and have little bearing on the real world.

Impasse (1967) - Director: Yoshishige Yoshida - 4/10 - This is where things get really dicey. Formal toying with characters truly intensifies here which practically results in the annihilation of any drama whatsoever. The heroine cannot get pregnant by her husband because of his impotence which is a symbolic manifestation of her being alienated from her role as a mother as well as a wife… you get the picture. None of this is really all that engaging unless you are genuinely keen on some demented New Wave filmmaking. While the monochromatic cinematography looks gorgeous, the film itself is somewhat… well… tedious to be perfectly honest.

Woman of the Lake (1966) - Director: Yoshishige Yoshida - 7/10 - This thing is based upon a novel by Kawabata if I recall correctly which basically means there is some story at the center of it and therefore, it does have some characters and not arbitrary, immaterial constructs no one gives a shit about. The tale recounts a story of a woman who has an affair with some chap who is also engaged to another female, unbeknownst to her. Once her nude pictures are seized by some random bloke, the couple assumes it’s all about the money and they want to pay him off, but it turns out the supposed blackmailer has something entirely else in mind. While the ephemeral quality of love is the primary subject matter of the novel and perforce the film in question, Woman of the Lake does touch upon Yoshida’s trifurcate outlook on female nature I’ve already described above. The film works owing to the combination of Kawabata’s prose, Yoshida’s elusive, ephemeral aesthetics and the peculiar atmosphere this odd marriage produces.

Affair in the Snow (1968) - Director: Yoshishige Yoshida - 5/10 - I could basically regurgitate the points I’ve made with regard to Impasse and they would still fit the basic premise and the kind of shit we’re dealing with here. The reason why I give it one more star is because it’s gorgeous to look at. It’s too bad there is nothing to take delight in other than landscapes and silhouettes of people, forget about characters or things like that. Oh, and by the way, it’s the same shit: Yoshida’s trifurcate take on femininity or whatever.

Farewell to the Summer Light (1968) - Director: Yoshishige Yoshida - 8/10 - I really like this one. Definitely the most European film Yoshida has ever directed: the entirety of the work just oozes with Resnais and there are lots of parallels between this effort and Resnais’s Hiroshima mon amour. The film revolves around a romance between a Japanese tourist searching for a European cathedral depicted on one of Japanese medieval Christian engravings and a female who is married to a wealthy American and spends most of her time collecting art and antiques. The impressionistic quality the film exudes, again, indicates the irrational trait of perceiving time. This matter also relates to the topic of Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings which are then reminisced about by the central couple. While there is nothing quite all that substantial about the film, the thing that I thoroughly cherish about it is the fleeting, evanescent flavor of the narrative alongside the warm, mellow cinematography, whereby Yoshida lavishly suffuses its viewers with balmy, sunny hues. Some English dialogues are dubbed horrendously, but fortunately there aren’t all that frequent.

I need another coffee.

Intentions of Murder (1964) - Director: Shohei Imamura - 7/10 - A re-watch - Another Imamura’s film in which the central heroine, Sadako, functions as a sort of essence of Japanese culture (again). The female of course comes from a rural background which means she is completely disempowered within the Confucian framework of the institution of family. Sadako is legally not entitled to take care of her own child and is always supposed to do her husband’s bidding with no right of objection despite the fact that her spouse clandestinely has a lover on the side. One day, she is raped by an intruder. Her rapist keeps revisiting her, but he grows more benevolent in his attitude towards her which at the same time makes him one of the most benign people within her milieu. This odd situation makes her realize her underprivileged position and she takes appropriate measures which results in her finally obtaining custody over her own child. While not as enjoyable as two abovementioned Imamura’s pics, it’s still very engaging in its own quaint way. Worth a look.

Double Suicide (1969) - Director: Masahiro Shinoda - 8/10 - A re-watch - A movie about a paper merchant who wants to commit suicide with his lover and a courtesan. Definitely one of the most unusual movies I’ve ever seen. The motion picture is based on an extremely famous play by Monzaemon Chikamatsu. One of the reasons why Shinoda decides to experiment with this material is because it’s extremely well-known in Japan in the same way Shakespeare is renowned in the West. Shinoda merely implements the general premise in order to juxtapose the Japanese status quo of the 1960s with the Edo period which is done so as to inspire social change and eradicate social stagnation racking the society at large. Furthermore, Shinoda endows his movie with an exceptional aesthetic foundation drawing from all kinds of sources ranging from ukiyo-e paintings, manga comics and kabuki as well as bunraku theaters. This staggering amalgamation renders it probably one of the most remarkable feats in the history of Japanese filmmaking on the whole.

Shinoda, for instance, locates the vanishing point of most frames beyond the reach of camera, instantly evoking two-dimensional aesthetics similar to those of Japanese graphical arts prior to importing the Western concept of perspective which irrevocably impacted ukiyo-e artists. Therewith, the director borrows kuroko (puppeteers) from bunraku theater: these literally operate characters on the screen in the same way puppeteers would control puppets in normal circumstances. This maneuver is intended to embody miscellaneous impalpable powers that inescapably influence one’s fate within a larger, societal context. Most of the action is shown within confines of an arbitrarily erected set consisting of paper walls covered with kanji marks and plays’ librettos which is, again, deployed with a view to alienating its audience in a classically Brechtian style and helping the audience perceive the social state of affairs more pellucidly without excessively empathizing with protagonists and thereby, losing track of the implicit meaning of the spectacle. Once lovers set off for their final destination: a cemetery, where they will both commit suicide, film’s theatricality in the form of the abstract set is shattered and the rest of the plot is filmed in the real world which goes on to show that the staginess personifies societal structures. I guess that’s the gist of it. I’m too much of a pleb to consider it one of my most favorite films, but it’s a very impressive movie overall and I liked it a lot more this time around. The entirety of the pic isn’t exactly thrilling at every single point, but you get the idea. Let’s put it this way: there is nothing quite like it. It is very peculiar and very good.

Eros Plus Massacre (1969) - Director: Yoshishige Yoshida - 8/10 - The movie at hand is very analogous to the aforementioned Double Suicide in the way in which it juxtaposes the past and the present, likening Japan’s radical Left of the 1960s to political radicals of the Taisho era. The central subject matter of Eros Plus Massacre is the idea that shaping the future can only achieved through reflecting on the past and the present. The main hero of the movie is a female student that researches the life and death of Osugi Sakae, an anarchist that was slaughtered by the Japanese authorities in the aftermath of the great Kanto earthquake from 1923. Sakae was slayed on account of his radical ideas that directly confronted the state and therefore, he constitutes an ideal person through whose prism one can muse on the status quo and foster an appropriate social change. Yoshida implements multiple Brechtian techniques, such as including theatrical interpolations and intermingling the past with the present. Yoshida quite assiduously and elaborately emphasizes the fact that the presented past is nothing more than a projection of the main hero’s mind which is intended to punctuate the distortions that the mere process of narrativization of history entails. Yoshida likewise explores ‘unrealized’ versions of Osugi’s death.

All in all, the movie is a fascinating phantasmagoria of a movie, an avantgarde experiment of epic proportions. Despite being mammoth in its length, it is surprisingly engaging by virtue of its sheer eccentricity and visual beauty. Visually, it is Yoshida’s most advanced and sophisticated work. The cinematography is just phenomenal and incomparably distinctive. Most frames are radically decentered, occasionally extremely angular, with a lot of headroom; Yoshida’s typically monochrome palette acquires characteristically bleached feature. The overexposed quality of many scenes in conjunction with musique concrete soundtrack as well as the arbitrarily episodic structure all make for an unforgettable experience. Notwithstanding, the element that I find particularly engrossing is the presence of well-delineated characters - personas of Osugi as well as his lovers are very deftly depicted and the portrayal of his ideological clash with the state provides a lot of insight into the inner workings of the Taisho radical movements in the advent of progressively metastasizing prewar militarism.

Nanami: The Inferno of First Love (1968) - Director: Susumu Hani - 9/10 - A re-watch - I liked this one a lot. This movie provides probably one of the most introspective, imaginative and visually evocative explorations of the human psyche I’ve ever come across. There is just something unique in the way that Hani constructs images and links them with concrete states of mind. That is not to say that the movie is nothing but visuals. While the plot is heavily decentralized and the storytelling has a somewhat impressionistic quality to it, the movie has two extremely likable characters at its core. The boy, Shun, is an orphan who was adopted by a pair of middle-class citizens. His father regularly molests him as a consequence of which he finds it difficult to form meaningful relationships and connect with the rest of the world. The girl, Nanami, works as a nude model for an agency that specializes in erotic photography. Shun endeavors to dissuade Nanami from working for the agency because he regards her work as demeaning. The movie, by and large, dissects Shun’s as well as Nanami’s internal lives, but Hani likewise dedicates some running time to unrelated topics.

The Man Who Left His Will on Film (1970) - Director: Nagisa Oshima - 7/10 - A re-watch - Another psychedelic trip of a film. The plot doesn’t make much sense, because it is in and of itself a never-ending loop. It’s hard to delineate one storyline as such, suffice to say, Oshima’s effort focuses on the contradictions of political cinema, his inability to link his filmic language with political ideas as well as the crisis of the political filmmaking as such. It’s got wonderful cinematography and beautiful, luscious soundtrack (it’s Takemitsu, so no wonder). It’s incredibly cryptic as well. I could naturally dissect individual scenes and highlight the underlying meaning of the plot, but it would take some time and I don’t pretend to comprehend all of it and this post is long enough anyhow and I’m a lazy ass.

Heroic Purgatory (1970) - Director: Yoshishige Yoshida - 5/10 - This movie is even more plotless and constitutes a veritable phantasmagoria of a motion picture. The movie mostly deals with the issue of the decline of Japan’s radical Left, but there are no characters, no straight-forward storyline and no clear meaning to speak of. The movie somehow works because of its dreamlike quality and the immense visual beauty typical of Yoshida. It’s too bad there aren’t more overexposed scenes like in Eros Plus Massacre.

The Ceremony (1971) - Director: Nagisa Oshima - 5/10 - A re-watch - While it’s a historically significant film, it’s somewhat difficult to watch. That is not to say it’s vapid or something along those lines, as there are some truly amazing scenes in there such as brideless wedding ceremony. Nevertheless, on the whole, there are more enjoyable Oshima movies out there.

Coup d’Etat (1973) - Director: Yoshishige Yoshida - 7/10 - A biopic about a national socialist and a panasianist Ikki Kita who was linked to the Feburary 26 Incident in which a group of military men attempted a coup d’etat. Yoshida uses the basic premise of the historical event to touch upon the disillusion of the younger generations in the elders who cynically used their youthful enthusiasm and vigor for their political ends. Ikki in the film cannot live up to the ideals he espouses and ultimately is betrayed by an anonymous young soldier disappointed with Kita’s stance during the attempted coup. Despite being a lot less experimental in its form, the motion picture still has a strong Yoshida’s vibe to it with an abundant number of decentralized frames, a dense, virtually miasmic atmosphere and a characteristically monochrome palette.

Hostile Waters (1997) - Director: David Drury - 6/10 - While there is nothing inherently great about it and the film stays fairly basic throughout its running time, there is something uncannily entertaining and effedtive about it. Also, the acting remains strong through the entirety of its length. I really like those frugal, but effective HBO productions from the 1990s. Me likey.

U Turn (1997) - Director: Oliver Stone - 5/10 - I’m not exactly sure what to say about this. I watched it primarily because it’s a neo-noir and I intend to watch all these things. Most necessary ingredients are here, but something is missing. Stone’s excessive stylization rubs me the wrong way sometimes and gets in the way of creating a truly stylish movie. It’s like Stone is constantly obsessing over his style, trying to endow his work with as many stylistic signatures indicative of his direction as possible. Characters likewise aren’t all that interesting in the first place.

Elegy to Violence (1966) - Director: Seijun Suzuki - 7/10 - It’s apparently considered to be one of Suzuki’s most important works, I guess it’s good enough. It’s pretty diverting most of the time. It’s pretty similar to Yoshida’s Coup d’Etat in the way it portrays the hypocrisy of the Japanese establishment cynically channeling sexual energy of young Japanese men into palpable military actions. I prefer Suzuki’s films with Shishido in the lead to be honest, this one is still pretty good though.

Solo: A Star Wars Story (2018) - Director: Ron Howard - 3/10 - Fuck, another Star Wars movie. I mean Disney really outcompetes itself at sequentially pumping out terrible Star Wars flicks, this one being the worst of the lot so far. There is a shitton of plot holes in here, most of it is scripted and narrativized in such a paltry fashion it really makes you wonder who on earth okayed this piece of shit and allowed to release it in the first place. Most of it simply looks like a high-budgeted Star Wars Christmas special. If you’re looking for a ruggedly recounted tale, look elsewhere. Disney has effectively butchered this franchise for me. Please, George, come back.

The Fourth Protocol (1987) - Director: John Mackenzie - 8/10 - I like this one a lot. Not sure why it’s not more renowned, it’s got all ingredients I want in a deft spy thriller.

Death and the Maiden (1994) - Director: Roman Polanski - 8/10 - Another Polanski’s stagey belter. The acting and the direction are both spot on. I love the ending scene.

Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) - Director: Rupert Wyatt - 6/10 - I thought it was okay. All of these ape movies are relatively well made, but this one is definitely inferior to the rest of them. The script here is just more run-of-the-mill and predictable to my way of thinking, the direction isn’t any better. The thing that redeems the film and overshadows its shortcomings is the fact that it’s incredibly entertaining most of the time, even if on a purely cursory level.

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) - Director: Matt Reeves - 7/10 - Like I said before, it’s better than its predecessor and the screenplay feels somewhat more polished and overall less formulaic. It works really well as a post-apo movie and the action here isn’t completely divorced from reality which helps a lot.

Sicario: Day of the Soldado (2018) - Director: Stefano Sollima - 7/10 - A surprisingly good follow-up to the original. I wish main characters were more fleshed out, but other than that, the film captures the magic and the grittiness its predecessor provided in spades. Again, so many critics are full of shit.

The Human Condition (1959) - Director: Masaki Kobayashi - 9/10 (8/10; 9/10; 10/10) - A re-watch - It’s extremely interesting to watch this film because of how Kobayashi’s filmmaking evolved throughout its production which took about 3 years. The first part’s direction gets out-of-focus sometimes and apart from that the Chinese dialogues sound awful. The second part is an excellent depiction of the military culture and the way it shapes the main character, while the third part is an absolute masterpiece showing the ordeal of Japanese citizens and military after the end of WWII. This is the first time I watched the entire movie in one sitting, it was well worth it.

The Fossil (1975) - Director: Masaki Kobayashi - 9/10 - I finally managed to get my hands on a copy of it and I wasn’t disappointed to say the least. It’s superior to Ikiru by a large margin and makes Kurosawa look like a child in comparison. Instead of a miraculous transformation of its central hero, Kobayashi’s opts for a more realistic, objective attitude and chooses to portray his protagonist as an everyday man with not a scintilla of pretentiousness that can be discerned in Kurosawa’s film. Often described as an anti-Ikiru type of movie, The Fossil revolves around a successful company executive who resolves to take a trip to Paris where he finds out that he suffers from stomach cancer. Initially, he is aghast at the whole situation. Upon the realization that he is soon going to die, he decides to take an excursion to Burgundy where he gradually begins to accept his condition. The film focuses on the inner dialogue of the hero who converses with the persona of death impersonating a middle-aged Japanese woman. She reminds him of various facts and events from his life which prompts him to reflect on his past and most importantly, his failures and slavish dedication to work with little regard for his beloved ones. Instead of Kurosawa’s somewhat infantile, materialist attitude, Kobayashi accentuates the meaning of art and spirituality in formation of one’s consciousness. The director doesn’t perforce refer to one specific religion or artistic tradition and merely endeavors to note the importance of art and spirituality in perceiving one’s environment. The movie doesn’t really take any decisive stances though, as it merely conducts inquiry into the fleeting nature of life experience in the light of impending death. Protagonist’s sense of time is heavily warped, and his perception is heightened on account of his acute awareness of physical impermanence and evanescence. The voice-over, which I usually abhor, greatly amplifies the atmosphere and actually allows Kobayashi to distance the action at hand, framing it within a larger metaphysical context and punctuating the ephemeral quality of life and individuality even more. Apart from that, the film boasts immense visual beauty and a stunning soundtrack by Takemitsu, which probably constitutes one of his most impressive achievements as well. No idea why it’s not widely available in the West, as it really is a terrific movie, but then again the same could be said about Kobayashi’s Inn of Evil. I’ve only scratched a surface here, this post is bloody long as it is, so I’ll leave it at that.

War on the Planet of the Apes (2017) - Director: Matt Reeves - 7/10 - I like the snowy locations and all, but the movie occasionally does get a little too maudlin and schmaltzy to my liking, so I guess I like the second part best. It’s still pretty good though.

Venerable deed